Calcutta Mint, Introduction of Machinery,

1790 to c1802

|

In

1789, a major report about the coinage of the Bengal Presidency concluded

that the problems of batta as well

as counterfeiting, filing, drilling etc, could be overcome by the

introduction of coin production following the “European” method. John

Prinsep, of course, had already done this but most of his machinery and

skilled employees had been rejected by the |

||||||||||

|

The

designs of the gold and silver coins produced in the Calcutta mint by 1790,

were based on the coins produced in the Murshīdābād mint

before the British had acquired control. The major difference was that the RY

was fixed at 19 although the Hijri year continued to change annually. This

annual change continued until 1202 on the gold and 1205 on the silver coins.

Gold

mohur and silver rupee prior to the introduction of milling On

The Board agreed in

opinion with Mr Shore as to the principle on which he proposes the recoinage

of the rupees should take place, but previous to adopting them finally, think

it necessary to ascertain whether the machines and implements for coining and

milling money in the European manner are ready or can be procured or made in

this country, and whether there are any persons who are acquainted with the

manner of fixing them up and making use of them. The Mint Master and Lt

Golding being in attendance are called before the Board… The

coinage was to be undertaken in all four mints in Bengal: Calcutta,

Murshīdābād, Patna and Dacca and the mint master, Herbert

Harris, provided a list of equipment that he considered necessary for

undertaking the new coinage in the new way: 1

flattening mill 2

cutting machines 1

stamping press 2

milling machines for graining the edges of the rupees 12

brass ingots Implements to be made to complete the

machines for four mints 3

small cutting machines 2

stamping presses 7

milling machines for graining To be purchased 2

flattening mills Implements ready in the mint 2

flattening mills complete 1

small cutting machine 4

large cutting machines 2

stamping presses complete Lieut Golding being

asked whether with the assistance of the artificers in the arsenal, he could

make all the above machines and implements for coining money in the European

method, he replies that he is of opinion that he could make them without

difficulty and that he entertains no doubt but that he could put them up. Being

asked in what time that machines for one mint could be completely put

together so as to commence the coinage of money, he replies that it could be

done in considerably less time than three months, and refers to a drawing of

the machines delivered in by the Mint Master and executed by Mr Aspinshaw,

the foreman of the mint, from which it appears that in three months one

machine complete might be put together and rooms built for the reception of

it. The

Mint Master being asked whether there are any persons in this country who are

acquainted with the mode of coining money in the European manner, he replies

that there are two under his department, Mr Aspinshaw, the foreman of the

mint, and his assistant, Benjamin Hughes; that the former is at present

dangerously ill, but that the latter is now in attendance. Benjamin

Hughes being called before the Board and asked if he was ever employed in any

of the mints in Europe, replies that he never was, but that he is acquainted

with the method of coining money, as practiced in Europe, having been

employed by Mr Binseh (Prinsep?) at Pultah in the late copper coinage, which

was performed with machines and according to the European method. Being

asked whether he is acquainted with the mode of putting together the European

coining machines, he replies in the affirmative. Being asked whether he

understands the mode of milling or graining money and whether he could make

the machines required for the purpose, he answers in the affirmative to both

questions. Being

required to state whether he could cut the screws for the fly presses, he

replies that he could. Ordered

that Lieut Golding be directed to proceed without delay to make such parts of

the machines and such of the implements as are of the most difficult

construction in order that there may remain no doubt of the practicability of

making the machines and apparatus for completing the recoinage of the silver

in the manner proposed. Both

Mr Aspinshaw and Mr Hughes had worked for Prinsep at Pultah and it is notable

that Aspinshaw produced the drawings for the new machinery, although he died

very soon afterwards, and Hughes was instrumental in building many of the

machines and worked at the London was informed of the new project

in January 1790 [3]: In the 37 paragraph of

our letter, dated the 5th November, from the Revenue Department,

we referred you to our proceeding of 25th October upon the

defective state of the currency in this country. We have the honor to

transmit, in the packet of the In

April 1790 London sent a letter supporting the proposed new coinage [4]: We have traced upon your

records the various methods that have been adopted for putting a stop to the

exorbitant batta demanded by the shroffs and others on the exchange of silver

for gold – your endeavours to remedy an abuse of such generally pernicious

tendency are entitled to our warmest commendations. Your last dispatch of Lord

Cornwallis in his letter of the 2nd of August has given it as his

opinion that there appears to be no effectual remedy for the evil but a general

new coinage of all the circulating silver of the country into rupees, or

sub-divisions of rupees, of exactly the same weight, standard and

denomination, and his Lordship has assured us that he shall spare no pain and

neglect no precautions to accomplish, with safety, this salutary work. When

we consider the proposition simply, and without having regard to local

prejudices, our assent naturally, and, as it were, in an instant, follows the

proposal. But we wished to learn the opinion that may have been formed of it

by the natives and others upon the spot, and we are happy to find by the

reports of the several commercial residents and agents in the provinces,

entered on your commercial consultations of 22nd May last, and by

the opinion of the Board of Trade on the subject, that by the establishing of

only one single coin throughout the country, no inconvenience or loss of any

consideration is likely to weigh against its utility. If the reports of our

servants in the revenue branch (who we observe have been consulted) shall be

equally favourable to the project, we trust his Lordship will be able to

effect his purpose previous to his departure for In

the meantime work had been progressing on the machinery for the I have to request you

will lay before the Right Honble the Governor General in Council the

accompanying schedules of the machinery and work done in the mint since the

determination of his Lordship to strike the new coin after the mode practiced

in England. In addition to this we have in many instances had the tools to

make before we could begin the work. The

present pay of the die cutters in the mint is sicca rupees 185 per month but

to perform the cutting as neat as they can do it, two other men whose wages

amount to sicca rupees 120 per month are required for this mint alone, and

two men for each of the other mints. This will increase the establishment to

full 500 rupees per month. Mr Spalding who has been bred to the dye sinking

business has offered to cut the dyes for all the mints and employ and pay the

workmen for sicca rupees 500 per month, including his own wages, and I beg

leave to recommend that his offer be accepted as it will save the Company the

amount of his wages and we shall be always certain of having the dyes

accurately cut, and the same for every mint. Lieutenant

Humphreys having informed me of an opportunity of supplying the mint with

some very valuable tools, particularly in the dye sinking business, I have to

request I may be permitted to purchase them for the use of the mints. The sum

will not exceed sicca rupees 700. The

movement of the great wheel of the mill not being sufficiently quick to roll

out the quantity of gold and silver we shall require, and finding if I began

to coin immediately, I should in a few days be obliged to stop the business

to add another pair of rollers, I have with the approbation of Lieutenant

Golding, who constructed the mill, prepared the frame of another set of

rollers in such a manner as to fit them on the spindle of the present, by

which means, the wheel being very powerful, can turn both, and we shall have

separate rollers for the gold and silver or apply both to the silver as

occasion may require. As

soon as the new rollers are fixed, we shall begin to train the people in the

several occupations of flattening, cutting, filing, adjusting, milling and

striking in copper, till we get them expert enough at the business to

commence the new coinage. There

then follows a list of the machinery that had been built (see Appendix at the

end of this chapter). Mr Spalding seems to have been a great

find and managed to invent a new way of producing dies that required less

labour and would be difficult for forgers to copy, although he felt that he

should be well rewarded for his efforts [6]: Since I wrote you last

on the subject of dye sinking, I have made an improvement in the business

which will enable me to do as much in an hour as I would before in three

days. Some men would keep this improvement a secret but on the contrary I

make it my boast, being convinced no advantage will be taken of my candour. In

consequence of this improvement, I beg leave to make some alteration in my

proposal for salary. In my last letter I mentioned I would require natives to

assist me. Now I want none, tho’ I must recommend the Company keeping and

paying a native who I will instruct in the business, with the motive of

providing against my indisposition. In

my last I mentioned I would engage to sink dyes for all the mints. At the

time I wrote my letter, I was not aware of the probability of copper coin

being wanted, and consequently an additional number of dyes required. But

with or without the additional trouble of making dyes for the copper coinage,

I consider I merit sicca rupees 500 per month as coiner and dye sinker and

having found a method much more accurate than that of copying the dyes by

hand, a method (mine is) which must preclude the possibility of the natives

forging the dye. And

it ought to be considered the improvement I have made, instead of being any

additional expense to the Company, is a saving, as I don’t ask so much as

coiner and dye sinker as it would cost the Company for dye sinkers only,

supposing the natives capable of sinking the dyes in the manner they are

wanted, which however they are not. From

the extract above, it is apparent that a new copper coinage was under

consideration in 1790, although nothing further was done for several years.

It is also clear that Mr Spalding was responsible for centralising die

production in In

June 1790 the Calcutta mint master, Herbert Harris, explained why the new

coinage had been delayed and also informed the Board that he had identified

another of Prinsep’s ex-workmen who would be very helpful to him [7]: I have received your letter

of yesterday desiring I will inform Government when the new coinage will

commence and what is the cause of the delay. When

the first rollers were put up in order to try the mill, we found them very

defective in many places and discovered that one pair was not sufficient to

roll out the quantity of metal wanted, but as we every day expected new ones

from Mr Golding, I had hopes the machine would soon be completed, as we had

contrived the means of adding (with the concurrence of that gentleman)

another pair of rollers of a different size to be turned by the spindle of

the machine. To fit these we were obliged to make a new frame and cogs, also

the necessary rack work for adjusting the rollers. As the nice parts of this

could only be accomplished by Mr Hughes, the business proceeded slow. When

Mr Golding gave us notice of his having failed in the tempering of his rollers,

it was necessary to consider how we could carry on the business with the

present rollers, and it was judged expedient to construct a polishing

machine, drawings of which we had from England, for to repair and keep the

rollers in order. This machine is absolutely necessary were the rollers ever

so good as they grow rough from the silver passing through them and require

polishing every three or four months. Mr

Hughes is now employed making this machine and he declares it will now take

him 20 days to finish it. He has also forged a pair of rollers, one of which

is now turning in the lathe and has every appearance of being perfect, and I

hope in a few days to be able to acquaint his Lordship that we have succeeded

in tempering it. A

large stock of dyes was also necessary to be prepared before the coinage

could be begun as the steel is very apt to fly from the pressure of the

stroke. Mr

Spalding has pointed out to me a native who was bred up under Mr Aspenshaw in

the Pulta mint and has obtained some knowledge of dye sinking, and is a very

correct and ingenious workman. This man is at present in the employ of Mr

Howatt, the coachmaker, as a painter, but as many of this trade are to be got

in Calcutta, I see no hardship Mr Howatt giving him up, as the man wishes to

work under Mr Spalding who assures me with the assistance of this man he

shall be ready to commence the gold coinage in one month from this date. On

21st July Herbert Harris was able to inform the Governor General

that he would start minting the new gold coins in August 1790 [8]: I am to request you will

acquaint the Governor General in Council that I shall be ready to commence

the coinage of gold after the Europe manner after the first of next month,

and desire you will inform me whether the suspension laid on the coinage of

gold bullion the 3rd September 1788 is to be taken off. In

response, the Board issued the following advertisement: Ordered the following

advertisement be published in the Gazette in the English and country

language: The

Governor General in Council has directed notice to be given that his Lordship

has been pleased to revoke the order that was passed on the 3rd

December 1788 for suspending the

coinage of gold mohurs at the mint, and that from and after the 1st

of next month, August, gold bullion will be received there for that purpose

and coined without charge to individuals. It

is further hereby noticed that from and after the 1st of next

month, new milled gold money will be issued of the former weight and

standard, and the gold now extant of the Calcutta coinage will be recoined on

application at the mint, into gold mohurs of the new coinage, also into small

money, that is halves and quarters, for the convenience of individuals,

without any expense to them, and weight will be delivered for weight. The

new gold coin will be received by the Collectors of the revenue and other

officers of Government in payment of the demands of the Company On

31st July, Calcutta informed London that they were about to start

minting the new gold coins [9]: On the 21st

July we were acquainted by the Mint Master that he should be ready to begin

the coinage of gold after the Europe manner on the first of the following

month, and we caused our advertisement to be published for the information of

individuals declaring the conditions on which their bullion would be coined,

and authorizing the new gold to be received by the Collectors of Revenue and

other officers of Government in payment of the demands of the Company. Lieut

Isaac Humphrys and Lieutenant Golding, of the Engineer Corps have afforded

very ready and useful assistance in superintending the construction of the

machinery for the different mints, and inventing and executing some parts of

it, particularly the milling instrument. The Governor General has been

pleased to record his sentiments thereon, in our proceedings of the 21st

July and, at his Lordship’s recommendation, we have acquiesced in granting

such recompences which they had actually incurred, as we deemed them justly

entitled to. On

I request you will

inform his Lordship I have begun the coinage of gold mohurs after the Europe

manner, that some delay has been occasioned by circumstances which we could

not forsee. The proof impression of the dyes on copper were very neat and the

round of the coin well preserved, but when we came to give the impression to

the gold, which is very fine and soft, the boldness of the letters occasioned

the coin to spread out of the circle on receiving the stroke from the

stamping machine, and it became necessary to alter the dyes so as to make the

relief on the coin less prominent. We

had no sooner got the dyes ready and were going to work than we found the

house had sunk from the very heavy rains and were obliged to take down the

laminating machine and lower it so as to make it work again. As none of the

walls of the house are cracked I conclude the sink of the foundations has

been pretty equal and I hope it has not endangered the building. The

gold coins produced at this time were probably those catalogued by Pridmore

in his Bengal Catalogue (Pr 61) and herein numbered 4.1.

The

first milled gold coins Having

decided that the new coinage would be difficult, if not impossible, to

counterfeit, it is interesting to note just how quickly that happened (August

1791) [11]: …A case has lately

occurred which has occasioned some embarrassment and may in future be

attended with very great inconvenience. By the proceedings referred to in the

margin, you will observe that an attempt has been made to imitate the gold

mohurs of the new coinage, and considering the defective means which must

have been employed on the occasion, with some success. The

Advocate General’s opinion has been desired, whether any statute is in force,

applicable to this country, by which coiners or the utterers of false coin,

may be brought to punishment. In

August 1792 the Mint Committee was able to report [12]: The size, shape and

impression of the gold mohurs appear perfect, and fully equal in every

respect to the newest English guinea, or any of the gold coins in The

machines and implements for striking and milling the gold coin, if not

exactly similar, appear to answer those purposes as well as the milling and

stamping machines used in

Thus the production of milled gold coins proved relatively

straight-forward, and from October 1792 the daily output of gold coins from

the

Production

of gold coins at the The Silver Coinage at At

the meeting held on Notice is hereby given

that the new milled silver coin will be issued from the Honourable Company’s

mint from and after the 10th instant in payment of the produce of

all silver bullion sent to be coined. The

shroffs, money-changers etc are positively forbidden to deface, cut or clip

the edges of the new coin or to put any private mark thereon. They are also

prohibited from exacting any batta on the old nineteen sun sicca under pain

in either case of incurring such punishment as the Governor General in

Council may think proper to inflict. London

was informed that silver coinage would be started, but using the “old mode of

coinage” in November 1790 [15]: … and the silver coinage

has also been begun upon. We were under the necessity, however, of allowing

the old mode of coinage to be continued for some time until there should be a

certainty of carrying on the business of the coinage by the new mode to its

full extent, so that no interruption or unnecessary delay might take place,

to the injury of the merchants and shroffs, & that a free importation of

bullion might not be prevented. The

notice announcing the new milled silver coinage was premature. By February of

1791 it had become clear that using the laminating machines that had been

built to roll out the silver was more troublesome than had been anticipated.

The mint master therefore decided that producing the blanks by hand would be

a more effective way of doing things for the time being [16]: I am to request you will

acquaint the Honble the Governor General in Council that I have tried the new

method proposed by Mr Spalding of preparing the blanks by striking them with

a hammer to the proper size for milling, and tho’ this method required a great

many people yet it is preferable in many respects to the laminating mill and

approaches very near to the method practised by the natives. The

Calcutta mint was able to produce 2000 rupees worth of gold coin and 120,000

rupees worth of silver coin in a week [17], but

probably not milled silver, and in May 1791 the mint master was able to

answer the following questions [18]: Question: Supposing the

whole mint establishment solely employed in coining silver. What number of

rupees could be coined daily? Answer: The rupees at

present are made in the old way, and are struck with the fly presses instead

of the hammer, which alone is a great improvement; and in this manner I can

coin twenty thousand rupees per day. Q: Supposing the whole

mint establishment solely employed in coining gold. What number of mohurs

could be coined daily? A: The gold being coined

after the European manner it would take some time to perfect the people in

filing and adjusting the planchets, and I think five thousand gold mohurs per

day would be as much as I could perform. In cutting out the planchets, or milling

the edges, there is no difficulty. Q: Supposing the whole

mint establishment employed in coining partly gold and partly silver, what

number of mohurs and rupees could be coined daily? A: I now coin about 18

or 19,000 rupees per day in silver, and 500 gold mohurs. The proportion of

silver to gold coined is as 4 to 1 In August 1791, Bengal updated London on the progress

that had been made so far [19]: Our advices by the

Princess Amelia informed you that the new silver, as well as the gold

coinage, had been actually commenced. Everything relating to this subject,

either as it respects the mint established at the Presidency or at the cities

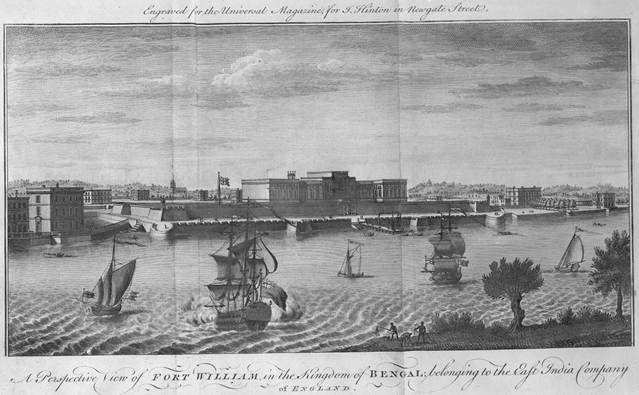

of The

buildings in the old fort, formerly appropriated to the use of the mint,

having been pulled down, and the temporary accommodations afterwards provided

for this purpose, being found exceedingly inconvenient, we complied with an

application made to us by the Mint Master for the hire of a house and

go-downs, which he represented as being well calculated for conducting the

business of his office in all its branches, at a rent which we presume will

be thought sufficiently moderate, being Sa.Rs. 400 per mensum. By

our orders of the 1st December 1790, and the 14th

January 1791, individuals delivering bullion into the mint were allowed to

take away immediately from the treasury the amount of its assay value; but,

in consequence of a representation made to us by the Accountant General on

the 21st of April, from which it appeared that the available

balance at the treasury fell short of the demands upon it for the discharge

of bills which would become due before the first of May ensuing, we were

under the necessity of suspending the operation of the orders in question

until the amount of bullion, deposited for coinage, should be diminished… …It

being important to ascertain with as much precision as possible, the quantity

both of gold and silver coin which, in a given time, could be worked off at

the mint, certain queries were proposed to that effect to the Mint Master,

adverting to the period when the buildings lately engaged for the purpose,

should be in a state of perfect preparation. These, with the Mint Master’s

answers, will be found recorded in the proceedings of the dates annexed… The silver coins produced at this time must have been the

19 sun sicca dumps dated AH 1205. Hijri year 1205 ended in August 1791, but

these coins seem to have been produced for a lot longer, probably until 1793

in By May 1792, it had become obvious

that the early optimism about the speed of implementing a machine-made silver

coinage was ill-founded. The In the same month, August 1792, the

Mint Committee was able to report [21]: …With respect to the

silver coin, it appears to be very defective with regard to its size,

thickness and impression. The blank is made with the hammer; the impression

is struck with a fly-press but with a die of twice the circumference of the

coin so that only a part of the impression appears upon it. The letters also,

instead of being flat like those of the gold mohur, are prominent and

pointed, and consequently liable to greater injury from common wear, as well

as from filing. From being very thick and not milled it may be easily filed

and drilled, and is liable to be defaced and debased in other ways, so that

no person can receive it with safety without having it examined by a shroff. We

beg leave therefore to recommend that in future the rupees be coined and

milled in the same manner as the gold mohur and that the Hijeree are to be

omitted, as the insertion of it, by shewing the year in which the rupees are

struck, defeats the object of Government in continuing the 19th

sun or year of the King’s reign upon the coin. We

beg leave to submit specimens of rupees coined and milled in the manner

proposed, and should they meet with the approbation of your Lordship in

Council, we shall take the necessary steps for preparing the requisite number

of fly-presses and other implements with the least possible delay, continuing

in the meantime to coin the rupees in the former method, until a sufficient

number of machines and implements are completed to enable the Mint Master at

Calcutta and the Assay Masters of the the other mints to coin the new rupees

with equal expedition. The

Board agreed with the proposals, notably that the hijra date should be

omitted, and they approved the specimens submitted. Further information on the production

process, and particularly when the milled coinage of rupees began in the

Calcutta mint, was given by the mint master, James Miller, in October 1793 [22]: …But since the

commencement of the milled silver coinage from and after the 31st

August last [i.e.

August 1793], the powers of the mint

have been greatly abridged in regard to the quantity of the whole coin that

can be produced in the same time, even with a considerable augmentation of

dye-feeders, lever-men etc, because of the increased quantity of labour which

is required in the new silver coinage beyond what was necessary in the old. At

present every blank receives three blows, one from a concave dye, another

from a collar dye and a third from the letter dye, which compleats the coin,

and between each of those blows the same blank must be annealed to soften the

silver so as to prevent its cracking towards the edge, until which caution

was observed, many blanks were obliged to be wholly reformed. In

the old way of coining silver, the duraps formed the blanks with a few

careless blows of the hammer, for, as they were not to be milled, it was of

little consequence whether they were perfectly round or not, and the diameter

of the rupee was chiefly determined by the force of the blow with which the

impression was made, and the ductility or hardness of the metal. But few

blanks were spoiled in comparison with those of the present coinage… From this information we can attempt to recreate the

process that was used in making the coins at that time. Blanks would have

been cut by hand and weighed and the weight adjusted. Then they were struck

with a concave die, probably in a collar, presumably to get them to the

correct diameter. Next they were struck with the “collar die” to “give a

smooth surface to the rim” (see p. 369). Finally they were struck with the

dies bearing the Persian inscription. Between each striking they had to be

annealed. This whole process was laborious and time-consuming. After this the

edge milling was added using a process that is not described but which, in

Calcutta, was carried out by boys from the orphanage [23]: The Mint Master at

Calcutta having applied to us for an additional number of boys to be employed

in milling the coin, we beg leave to request that your Lordship in Council

will be pleased to authorize us to apply to the managers of the orphan

society for four boys for the above purpose. As

well as agreeing that the Hijri date should be omitted and the silver coins

struck in the same way as the gold, Bengal reported to London in December

1792 [24]: Since the beginning of

October the Mint and Assay Masters have delivered into the Board a daily

return of work done at their respective offices, a measure of obvious

utility… …Towards

the end of October, the operations of the mint had become so much more

expeditious that we were able to revoke the permission granted on the 31st

August, to individuals delivering bullion at the mint, to exchange mint

certificates for 8 per cent promissory notes, instead of waiting to receive

in coin the produce of their bullion. This indulgence ceased from the 17th

November… As

stated above, the mint master had been asked to provide a daily report on the

activities of the mint, and this report included the number of coins struck,

by value. It is not possible to tell how many of each individual denomination

were struck to start with, simply a rupee value for silver. It seems likely

that only whole rupees were produced initially because, at a later date, the

number of half and quarter rupees is stated (see graphs below).

Grave of James Miller in , the mint

master at Calcutta, in Park Street Cemetery, Calcutta. (photo from Philip Attwood via Joe Cribb) Calcutta continued to produce the

blanks by hand, although a trial of laminating and cutting machines was

performed at the end of 1794 [25]: From the late enquiries

however, in which I have been engaged in regard to the flaws too often to be

found in blanks which had been fashioned by the hammer, I became sensible of

the necessity of endeavouring to bring into actual and constant practice the

mode of forming them by means of the laminating and cutting machines. Those

blanks which are formed by the hammer require and receive two separate blows

in the presses between what is called the collar and concave dies,

respectively, before they receive the last blow between the dies which give

the impression of the coin. Each of these blows renders the metal more rigid

and brittle, which causes the necessity of annealing all the blanks by making

them hot to redness, both between the first and second blows, and between the

second and third, which occasions not a little loss of time. Notwithstanding

the above method of softening the metal, it sometimes happens that blanks

which were formed even free from flaws when delivered from the hammer have

exhibited cracks more or less considerable, after each blow, and after having

sustained the two first, have under the last been rendered unfit to be issued

from the mint as coin. I

therefore caused a trial to be made of the laminating and cutting machines,

the blanks formed by which require no other blow in the presses than that

which gives the impression. This trial was made upon about 1000 Sa Rs, the

coin produced from which appeared to be most perfect in every respect, but of

greater diameter in a small degree than that which had been before approved

of. The cutting machines have been accordingly reduced, and I am now giving

out considerable quantities of the Dutch silver to be formed into whole

rupees in the above manner, to enable the Honble Board to judge of which, I

have herewith the honor to enclose two rupees of the coinage by the hammer,

one of the sort which I had found to be to large by the cutters and one of

those produced since the cutters were contracted. This

mode of coinage may, I am sensible, occasion additional expense in some

instances, whilst in others it will effect a considerable reduction, because

it will render about two-thirds of the pressmen and dye feeders unnecessary.

In the meantime I continue to occupy most of the duraps in the old way, and

only employ a few of the sardars in adjusting the blanks, which are formed

after the laminating method. The sardars however, I am sensible, would not be

friendly to the establishment of this mode of forming the blanks unless they

could obtain such wages for adjusting them as would compensate for the loss

of the docauns, and the advantages they derive between the wages they pay to

the people they employ, and the amount allowed for each set. But if this should

be the case, other people for adjusting the blanks must be sort for and

entertained. The

Honble Board, I cannot therefore doubt, will be satisfied that a change of this

nature must be effected by degrees and in such manner as not to occasion any

stop or impediment to the coinage…

An important point to note from the above extract is that

the trial produced approximately 1000 pieces, which were of slightly greater

diameter than the normally produced rupees. This observation is important for

attributing the different coins to their time of production (see below). In fact, The graphs on this and the following

page show that, like the gold coinage, the mint began by producing whole

rupees and, once this had been perfected, the mint concentrated on producing

the fractions. It is also interesting to note the reduction in coinage,

mentioned by the Mint Committee, following the introduction of the milling

process in 1793.

The

output of silver coins from the Regulation

for the New Coinage In

October 1792, following the review by the Mint Committee, the Governor

General published an advertisement formally announcing the new silver

coinage, and that, as from April 1794, the only coins acceptable as currency

would be the 19 sun siccas [26]: The following

regulations for the conduct of the several mints having been adopted by the

Governor General in Council are now made public, together with the subjoined

table of rates of batta for general information First: that after the 30th

Chyte 1200, Second: that public notice be given

that Government, with a view to enable individuals to get their old coin or

bullion converted into sicca rupees without delay, have established mints at

Patna, Moorshedabad and Dacca, in addition to the mint at Calcutta. Third: that for all bullion or old

coin of sicca standard delivered into the mint, an equal weight of sicca

rupees be returned to the proprietor without any charge whatsoever. Fourth: that all bullion or old coin

under sicca standard delivered into the mints be refined to the sicca

standard and that a number of sicca rupees equal to the weight of the bullion

so refined be returned, after deducting twelve annas per cent for the charge

of refining. Fifth: that the rupees coined at

Dacca, Patna and Moorshedabad be made precisely of the same shape, weight and

standard, and that they bear the same impression as the 19 sun sicca rupee

coined at Calcutta, in order that the rupees struck at the several mints may

not be distinguishable from each other, and that they may be received and

paid indiscriminately in all public and private transactions. Sixth: that to guard as far as

possible against the counterfeiting, clipping, drilling, filing or defacing

the coin, the dies with which the rupees are to be struck be made in future

of the same size as the coin, so that the whole of the inscription may appear

upon the surface of it, and that the edge of the coin be milled. Seventh: that persons detected in

counterfeiting, clipping, filing, drilling or defacing the coin be committed

to the criminal courts and punished as the law directs. Eighth: that all the officers,

gomestahs and others employed in the collection of the revenues, the

provision of the investment, and manufacture of salt, and all shroffs,

podars, zemindars, Talookdars, farmers and all persons whatsoever, be

prohibited affixing any mark whatsoever to the coin, and that all rupees so

marked be declared not to be legal tender of payment in any public or private

transaction, and that the officers of Government be directed to reject any

rupees of this description that may be tendered at the public treasuries. Ninth: that as there may not be a

sufficient number of sicca rupees in circulation in some districts

(notwithstanding the great number of this species of rupee that has been

lately coined in the mints at Dacca and Calcutta) to enable the landholders

to pay their revenues to Government in sicca rupees as stipulated in their

engagements for the decennial settlement, that the various species of rupees

current in the several districts be received at the public treasuries from

the landholders and farmers in payment of their revenue until the 30th

Chyte 1200 Bengal style, or 10th April 1794, at fixed rates of

batta to be calculated according to the difference of intrinsic value which

the various species of coins in circulation bear to the sicca rupee as

ascertained by assay in the Calcutta mint. Tenth: that all rupees excepting

siccas, which may be received at the public treasuries agreeably to the ninth

article be not on any account issued therefrom, but that they be sent to the

mints and coined into siccas of the 19 sun. Eleventh: that after the 30th

Chyte Bengal style, corresponding with the 10th April 1794, no

person be permitted to recover in the Dewanny or Maul Adawlute established in

the provinces of Bengal, Behar and Orissa, any sum of money under a bond, or

other writing, or any agreement written or verbal, entered into after the

above mentioned date, by which any species of rupee excepting the sicca rupee

of the 19 sun is stipulated to be paid. Twelfth: that persons who shall have

entered into bonds or writings or other agreements written or verbal, prior

to 30th Chyte 1200 Bengal style, corresponding with 10th

April 1794, whereby a sum of money is to be paid in any other species of

rupee excepting the 19 sun sicca, and who shall not have discharged the same

before that date, be at liberty to liquidate such engagement either in the

rupee specified therein or in the 19 sun sicca rupee at the batta which may

be specified in the table mentioned in the 9th article. Thirteenth: that all engagements

hereafter entered into on the part of Government for the provision of the

investment or manufacture of salt or opium, be made in the sicca rupee, and

that all landholders and farmers of land be expressly prohibited from concluding

engagements with their under renters, ryots or dependent talookdars, after 30th

Chyte 1200 Bengal style, corresponding with the 10th April 1794,

excepting for sicca rupees, under the penalty of not being permitted to

recover any arrears that may become due to them under such engagements as

prescribed in the 11th article. The low production of silver coins caused the date for

the introduction of this regulation to be moved to 1795 [27]: The Governor General in

Council, taking into consideration the above letters, observes that similar

representations have been received from other parts of the country of a want

of a sufficient number of the nineteen sun sicca rupees, to make them the only

legal tender of payment, and as the attempting to enforce this part of the

regulations until a sufficient quantity of that species of coin has been

introduced into the circulation, would be the source of much inconvenience

and oppression to individuals, he resolves to postpone to the 10th

April next the operation of that part of the thirty fifth regulation passed

in 1793, by which the receipt of any rupees

excepting siccas of the nineteenth sun is prohibited from the 10th

April last, and that in the meantime rupees of sorts be received in payment

of the public revenue under the rules which were in force prior to the last

mentioned date. Attribution

of the Type 1 Rupees to a Date The

silver coins produced during the 1790s are recorded by Pridmore, and consist

of three types shown in the pictures below. One point that needs to be considered

in assigning the type 1 rupee to its date of issue, is the statement from the

records, cited above, that a trial of laminating and cutting machinery was

undertaken in the

Type

1: Broad rim, Hijri date 1202 (actual size)

Type

2: Narrow rim, Hijri date 1202 (actual size)

Type

3: Narrow rim, no Hijri date (actual size) From

these results, it seems reasonable to conclude that the type 1 rupee can be attributed

to this event in 1792, and not to the 1790 experiments. The type 2 coins were

probably produced from the middle of 1793 until the middle of 1794, when the

type 3 coins began to be produced. This last type continued in production

until 1818. Although

the preparation of a new copper coinage had been discussed on and off for a

number of years, the mint was preoccupied with producing sufficient gold and

silver coins to standardise the coinage of the Presidency. It was not until

1794 that the assay master at the In 1795, the Governor General, The present very

defective state of the copper coinage has long been a subject of general

complaint, but particularly amongst the lower orders of the people, on whom

it occasionally operates as a heavy grievance... …This

constant fluctuation in the value of the copper coin, is a source of great

profit to the shroffs who combine to raise and fall the value of it in the

different parts of the country, buying it up when they have depreciated it,

and selling it at an enhanced value when they have accumulated so large a

quantity as to render the remainder in circulation at the places to which

their influence may extend, insufficient for the dealings of the inhabitants.

Exclusive of this source of advantage, they likewise derive a large profit

from trafficing with the numerous sorts of old and counterfeit pice which

have local currency in the different parts of the country in the same manner

as by the exchange of the old copper. Shore

then went on to explain how the copper coinage had been operated by previous

administrations: Previous to stating any

propositions for a new copper coinage, it may be necessary to notice the

principles upon which the copper currency was regulated under the native

administration and the rules that have been prescribed regarding it by the

British Government. Under

the Mogul administration the silver coin was the only measure of value, and

legal tender of payment. Gold mohurs and pice were struck at the mint for the

convenience of individuals who carried gold or copper to be converted into

those coins. But the Government never fixed the number of pice which should

be considered as equivalent to a rupee, any more than the number of rupees

that should pass in exchange for a gold mohur. Like other commodities, the

gold and copper coins were left to find their value in the market, compared

with the common standard of valuation, the rupee. As

a necessary consequence of the above principles, the quantity of copper

contained in the number of pice exchangeable for a rupee, was in general

nearly proportionate to the price of copper in the market, or in other words,

the nominal and current value of the coin was nearly the same as the

intrinsic value. From

the year 1772, when the mints at Next

he discussed the requirements for the new copper coinage: …The desideratum in the

copper coinage of this country, is that a given number of the coin should

pass universally for the fractional part of a rupee, or perhaps half a rupee

or eight annas, and no more, in all purchases or payments whatever. To effect

this desirable object, the following appear to be the principles on which the

copper coinage should be regulated. The

intrinsic value of the coin should be nearly equal to its nominal worth

estimating it according to a moderate average price, so as to preclude

individuals from deriving any advantage from counterfeiting the coin. This is

the great evil to be avoided, but which would be the necessary consequence of

estimating the copper at too high a value and prevent the coin being

generally received at its fixed value. On the other hand, supposing the

copper be rather under valued, it can only produce the effects of occasioning

some of it to be milled down when particular circumstances may cause an

unusual rise in the price of copper. This however can rarely happen to any

great extent; at all events it is an evil of comparatively little importance,

being attended in its consequences only with the trouble of throwing a

further quantity of the coin into circulation, the additional quantity of

copper required for which can always be imported with advantage from Europe. The

type and cost of copper was considered: The sheet copper is the

proper sort of copper for coining into pice. From the annexed statement it

appears that the average price of this copper at the Company’s sales for the

last ten years, is current rupees 46:1:1½ per factory maund of sicca weight

72:11:7 to the seer. The price however has arisen at different times within

the above period considerably higher and at the sales in January 1794 it was

near forty eight current rupees. As

the basis therefore for calculating the intrinsic value of the coin, and

fixing the proportion between that and its nominal value, it might not be

advisable to assume a higher value than forty five current rupees. He

then calculated a suitable weight for a pice and half anna, concluding that

this latter denomination would be too heavy for practical purposes and that

the coinage should therefore consist of pice and half pice: The factory maund contains

2880 sicca weight; supposing a pice to be struck weighing sixteen annas, it

will consequently give 2880 pice to the factory maund. If these pice be

valued at a quarter of an anna each, or sixty four for the sicca rupee, they

will have a value in circulation of exactly forty five sicca rupees the

maund, which will be sixteen per cent more than the intrinsic value of the

copper, estimating it at the proposed price of forty five current rupees each

factory maund. This

difference will be sufficient to cover the expense of the coinage, without a

probability of any inducement being afforded to individuals either now or

hereafter, to counterfeit the coin. Pice

therefore of the weight and issued at the value above specified, would be

sixty per cent more in weight & consequently in value than the pice now

issued at the same value. A

half anna pice of thirty two annas weight would be too heavy a coin for

circulation, and any smaller subdivision of a rupee than a one hundred and

twenty eighth part appears unnecessary, as in transactions in which a smaller

sign of value are required, the cowries are invariably used throughout the

country. It appears expedient therefore that there should be only two

descriptions of copper coin, a whole and a half pice, the former to pass at

the value of a quarter of an anna, & the latter at half a quarter of an

anna. There

can be no objection to the receipt of these coins upon the ground of their

being over valued in the proportion above stated, for altho’ it is necessary

that the intrinsic and nominal value of gold and silver coin should be the

same, the observance of this rule is not equally necessary with copper coin,

especially when declared as hereafter proposed, to be current for the

fraction of half a rupee only. There can be little doubt therefore that under

proper regulations, pice and half pice of the weight, and issued at the value

above proposed, would be received throughout the country, at that value, and

consequently remove the cause of the heavy grievance above complained of by

the furnishing a convenient circulating medium for the petty transactions of the

lower orders of the people, which will exempt them from the impositions they

now suffer from the money changers. The

Governor General then went on to lay out proposed regulations for the copper

coinage. Firstly he set out what the coin should look like: These regulations are in

abstract as follows: That people in all parts

of the country may be apprized of the value at which the coin is issued by

Government, & to be received and paid by the public and by individuals,

the value should be inscribed on one surface of it in the Persian, Bengal and

Nageree, the three characters used in business in the different parts of the

provinces. Secondly

he proposed that copper coins should only be accepted in payments of up to

half a rupee (eight annas) in value: Instead of obliging

individuals to receive copper to the amount of one per cent as at the last

coinage [i.e.

Prinsep’s copper coins, see chapter 3],

the coin should be declared a legal tender of payment for the fractional

parts of half a rupee, or eight annas, and no more, & all the offices of

Government should be prohibited receiving or issuing any larger amount in

copper, in receipts and disbursements made on the public account. Thirdly,

coinage would be confined to the As the coin is to be

made on account of Government, it should be struck at the On

the preceding regulation it may be observed that no estimate can be formed of

the probable extent of the demand for the new pice, as there are no data for

calculating the quantity of old pice of various sorts now current, and

supposing it could be ascertained, it would be no criterion for judging of

the quantity of new pice that may be required for the circulation of the

country, should they become generally current. He

then discussed the method by which the coins would be put into circulation: To facilitate the

introduction of the new pice, and to prevent any inconvenience arising from

withdrawing the old pice from the circulation, a quantity of the former

should be prepared previous to the publication of the intentions of

Government to establish the new coinage, & sent to the General Treasury,

the collectors of the revenue, the commercial residents, the salt agents and

the collectors of the Government and Calcutta customs, with directions to

dispose of them at the rate of 64 whole pice or 128 half pice for the sicca

rupee, to any persons who may be desirous to purchase them at that rate.

These officers however should be prohibited from receiving in any payment

which may be made to them on the account of Government, or issuing in any

public disbursement, a greater sum in pice than the fractional parts of eight

annas in each receipt on payment. When

any of the officers above mentioned shall have occasion for a supply of pice

for the circulation, they should apply for them to the Governor General in

Council through the regular official channel, submitting at the same time the

grounds of the application. They should at the same time be enjoined to be

particularly careful not to dispose of them to the shroffs in large

quantities so as to enable them to derive an advantage from the sale of them,

but to endeavour to distribute them as much as possible throughout their

respective district to persons who may have occasion for pice for their

private disbursements, and not to make a profit by disposing of them. Next

he discussed receiving old pice into the treasuries and, interestingly,

refers to “ As Government cannot in justice

refuse to receive the After

the period specified in the preceding article, neither the old Calcutta pice

mentioned in the 5th article, nor any other pice (excepting the

new pice) should be received at any of the public treasuries or offices, or

issued therefrom on any account whatever, nor should they be legal tender of

payment for any sum in any public or private transactions. All

public officers should be prohibited issuing the old The

old pice which may accumulate in the public offices in consequence of the

preceding orders should be sent to the It

may be likewise necessary, to prevent the counterfeiting or defacing the

coin, that persons convicted of such will be committed to take their trial

before the criminal court and punished as the law may direct. By

the adoption of the above rules, the old pice will be withdrawn from

circulation without inconvenience to the public and the new pice be gradually

introduced, and in such quantity only as the circulation may require. He

then went on to consider the costs involved: From the annexed

statement furnished by the sub-treasurer, it will appear that the value of

the This

sum might be further reduced by instructing persons in the different parts of

the country to purchase the Calcutta or Prinsep’s pice on account of

Government, provided they can procure them at a low value, nor could the

measure be considered as an injustice to the public, as all persons who may

be in possession of any of these pice are at liberty by the rules above

proposed to pay them into the public treasuries at the full value at which

they were issued by Government. The Board however will hereafter take into

consideration the propriety of adopting this measure should circumstances

appear to require it... In accordance with this resolution, James Miller, the

mint master, prepared specimens of whole and half pice [29]: I have the pleasure to

send you herewith four specimens of each of the copper coins, as directed in

your letter of the 2nd ultimo, for the inspection of the Honble

Board. In

November 1795, the Governor General approved the coins and instructed the

mint master to begin production: I am directed to

acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 6th instant and to

acquaint you that the Governor General in Council approves of the samples of

the whole and half pice which you have submitted and desires that you will

make the necessary preparations for the new copper coinage with all

practicable dispatch. You

are to coin an equal value of the whole and half pice until it shall be

ascertained which of the two coins are likely to be in the greatest demand

for circulation, when the future proportions of each may be regulated

accordingly. The

Board of Trade have been directed to allow you to examine the sheet copper in

the Company’s warehouse and to retain from the quantity now in store, and the

expected imports of the current season, three thousand factory maunds of the

sort which you may select as most proper for coining into pice. These first specimens probably had the inscriptions ek pau anna (a quarter of an anna) and

nīm pau anna (half a

quarter of an anna) because the Governor General agreed that this should be

changed [30]: The Governor General in

Council understanding that the relative value of the whole and half pice with

respect to the sicca rupee will be better understood by the natives in

General and especially the lower orders of them, by substituting ek pai sicca

(one pice sicca) and adh pai sicca (half a pice sicca) for ek paow anna (a

quarter of an anna) and neem paow anna (half a quarter of an anna), the

inscription ordered on the 2nd ultimo, resolves that instructions

be issued to the Mint Master for that purpose. The method of producing copper coins was found to be more

difficult than first envisaged [31]: In the idea that the

copper pice of which I transmitted samples to Mr sub secretary Barlow on the

6th instant will probably be approved by the Honble Board, I

directed some questions to the Foreman respecting the apparatus that would be

necessary for melting down about 215 maunds of old pice which have been

received from the general treasury and for recoining the same into new pice;

in answer to which I have received his observations thereon, which are as

follows: The

natives cannot melt copper sufficiently malleable to be made into pice. It

has been tried repeatedly but found not to answer either for the hammer or

laminating machines. The

best and least expensive mode of making the new pice is from sheet copper, by

the laminating machine. The braziers will (I believe) give something more for

the cuttings than for sheet copper as the former saves them the trouble of

cutting the copper to put into their pots when they make brass. Mr Prinsep

found this to be the case when he made pice. The

Durapps can cut down the old pice so as to answer for the new, but that is a

tedious mode. In

the same letter, the mint master found that he could get useful information

from some of the mint workers who had formerly been employed by Prinsep: I have since enquired of

some of the natives in the mint, who I learn had formerly been employed by Mr

Prinsep, and each of them corroborates the report of the foreman, that old

pice cannot be melted down sufficiently malleable for the purpose of forming

new ones, in which case I conceive it would be necessary to make use of sheet

copper from the import warehouse. It

seems however necessary that whatever may become of the copper of the old

pice they cannot be disposed of in their present form without again forcing

themselves into some degree of circulation, and that for this reason the old

pice should either be melted down or in some other manner so effaced that

they cannot pass as coin either of standard or of inferior valuation. In

regard to the cutting down of the old pice by the duraps, I am induced to

believe that if at all practicable, the expense and delay would both be

beyond all reasonable proportion, for exclusive of their being able to form

but a few in that way, if all of them were so employed, they could only work

upon them during the short time that may happen when neither gold nor silver

happens to be in the mint. Besides which considerations it is only the old

whole and half pice that could be so cut down, all the smaller old pice being

of less weight than the new ones. If

therefore the Honble Board should approve, I would recommend a supply of one

or two hundred maunds of sheet copper from the Import Warehouse, that in this

case I may lose no time in providing the additional servants and laborours

necessary for forming the new pice by the laminating machine, and in the

meantime the old pice can remain locked up in the mint until the best mode of

disposing of them may be determined on. The

mint master was ordered to make the new copper coins from sheet copper, and

to dispose of the Prinsep’s and Ordered that the Mint

Master be directed to coin the new pice and half pice from the copper which

may be obtained from the import warehouse and to melt down the Prinsep’s or

Calcutta pice which were sent to him from the general treasury, or cut or

deface them so that they cannot be introduced again into circulation as coin,

and to dispose of the metal or the cut or defaced pice to the best advantage. and

he sent examples of the sheet copper that he considered appropriate for

coinage, asking that it might be sent out from England in sheets one foot

square [32].

A little later he revised this and sent another sample of the copper required

[33]. However, even once the mint master got

the sheet copper from the Import Warehouse Keeper, he found that the cost of

producing the coins was much greater then he had anticipated. The copper was

valued at Rs 5,460-3-2 and produced Rs 5,394-8-9 worth of coins, amounting to

a loss of Rs 65-10-5. In a second experiment there was an even greater loss

and the only solution that he could identify was to reduce the weight of the

coins [34]: …If the new whole pice

were reduced to the weight of 12 annas each, and the half pice to six annas,

they would still weigh 20 per cent more than Mr Prinsep’s pice, for

thirty-two of Mr Prinsep’s whole pice were valued by Government at a rupee,

or half an anna each, and when struck were intended to weigh but 1 rupee 4

annas, which at the most gives 40 sicca weight per rupee. Whereas if the new

whole pice, valued only at one quarter of an anna each, were reduced to the

weight of 12 annas, and the half pice in proportion, the publick would

receive 48 sicca weight per rupee in 64 whole pice, or 128 half pice, of

better copper and more complete manufacture. In April 1796, the Governor General agreed that an experimental

coinage should be undertaken to see what the lower weight coins would look

like [35]: Ordered the Mint Master

be informed that the Governor General in Council desires he will coin as a

specimen a small quantity of the whole pice at the reduced weight of 12

annas, instead of 16, and the pice at 6 annas instead of 8, and that he will

submit a particular account of the expense… And

a few days later the specimens were duly submitted [36]: …I herewith beg leave to

submit musters of whole and half pice, weighing 12 As and 6 As each,

respectively… The

lower weight coins were approved, but at the same time the Calcutta

Government resolved to ask Unfortunately the mint did not have

the technical ability to re-coin previously minted pice, nor could they

re-coin the older Prinsep’s pice as discussed above, but reiterated yet again

[38]: …I however beg leave to

represent that I have found it no less impracticable to recoin the new pice

lately formed than it was to recoin the old pice of Mr Prinsep. I

likewise understand that the labour and consequent expense of defacing them

so as to admit of them being sold as copper in the bazar, without danger of

being used as coin, would amount to a very considerable proportion of their

value, and that melting would be equally ineligible by reducing the value of

the metal for common purposes, exclusive of the expense of servants, firewood

etc and injury to the furnaces. From

all that I have been able to learn on the subject, the best method that

occurs, if it shall be found practicable, would be to deliver over both the

old pice of Mr Prinsep, and those lately formed weighing 16 and 8 annas, to

the Commissary of stores to be applied to the making of brass, for ordnance.

In which case probably the small pieces into which the copper is divided

might render it no less eligible for the purposes suggested than if it were

in the sheet. The

smaller half pice proved problematic. The impression did not always show up

clearly and the mint master investigated various reasons, finally concluding

that it was the thinness of the metal used, that caused the problem [39]: Having observed about the

beginning of the present month, that the impression of the half pice was in

several instances, so faint as not to be distinctly traced on the face of the

coin, I minutely enquired into the cause, in the idea that it might have

proceeded from striking off too many pieces with the same dies, from

carelessness in the dye feeders and lever men, or from both these causes. I

found however that the foreman chiefly ascribed the imperfection to the

thinness of the copper from the reduced weight from eight annas to six annas,

and in consequence I had assented to his reducing the cutters so as to render

the half pice blanks somewhat thicker. A few maunds of this sort were

actually struck off, but as some parts of the letters of the dye did not come

within the edge of the coin, I was admonished that it would be considered a

palpable defect, and I therefore put an instant stop to this coin, nor has a

single piece of it been yet sent to the Treasury, nor will any be sent

thither unless from the difficulty attending the formation of this small

pice, they should be admitted of by the Honble Board. I

desired to know from the foreman whether new dyes could be made for the half

pice, of such diameter as would admit of a deeper and more distinct

impression, and I now beg leave to enclose copy of his answer with the

inscription he suggests, and from which the whole of the Nagry characters are

left out. I

should have thought it altogether unreasonable to have expected the same

precision as to the formation and weight of copper pice that would be

indispensable in either gold or silver, but I considered that all pice where

the difference of weight should exceed one anna in twelve (or above 8 per

cent), and whose circular form was rendered irregular by coiners, ought not

to be considered as falling within the difference that might be admitted

between the precision requisite to the gold and silver coin, when compared

with the copper, and that such defects indicated carelessness in the workmen. But

though the pice which have been coined contain more samples of this sort than

I could wish, I do not mean to trouble the Honble Board with any such, unless

they should be called for, as I have no other wish or object than to render

the pice as nearly as practicable, equal to the musters which were delivered

in to the Honble Board with my address of the 13th April last, not

doubting that every indulgence will be granted to such imperfections as are

unavoidable. The

points of present consideration however, seem to be confined solely to the

half pice of six annas 1st,

whether the Honble Board shall think proper to continue them of their

original size, agreeably to the enclosed sample of the general run of that

coinage, marked No 1, notwithstanding the faintness of the impression. 2nd,

whether six anna pice of reduced size, but struck with the same dies as per

the enclosed sample, No 2, would be admissable or not, and 3rd,

whether such alteration in the inscription as sent in by the foreman can now

be adopted with advantage and propriety The

Governor General ordered the mint master to reduce the diameter of the half

pice and, if this did not work, to prepare new dies; and, if the whole

inscription would not fit, then to remove the Persian rendition of the value,

leaving only the Nagri. Once this had been addressed, the mint master was

instructed to strike the copper coins in the proportion of 350,000 whole pice

to 150,000 half pice [40].

Finally, in July 1796, he was told to concentrate on the production of whole

pice, and not to produce half pice, which he had not done up to that point,

except as trial runs [41]. By August 1796, the attempts to

produce pice of 16 annas weight had resulted in a total production of 363,000

pieces of whole pice and 642,992 half pice. These had all been sent to the

treasury, but could not be issued because the lighter weight pice had by then

been produced and issued. These amounted to 1,226,000 whole pice and 605,000

half pice (despite the fact that he had been told not to produce half pice) [42]. By October, all of the copper

available had been converted into coins [43] and

it only remained to find a way of disposing of the sizel (copper scrap) left

from the coinage, and all of the heavy-weight pice that had been struck

initially. All of this was eventually sold as scrap [44]. Further coinages of copper took place

in December 1800 [45], May

1801 [46] and

October 1801 [47]. APPENDIX. Apparatus

built for the A

large horizontal cog wheel turning two vertical one[s] for working the

flatting mill A

fly press for striking the gold mohurs A

fly press nearly finished for striking rupees Fitting

up the fly press for the small gold coin A

cutting machine with table complete for the gold mohurs A

cutting machine ditto for half mohurs A

cutting machine for the small gold coin nearly finished A

cutting machine for the rupees with table complete Fitting

up an A

complete set of iron ingots moulds for the gold mohurs A

complete set of ditto for the half ditto Three

complete sets of ditto for the small coin 12

ingot moulds being part of what is required for the rupees 2

large tables for adjusting the planchets with 12 concavities for holding them

and 12 brass standard for suspending the scales with pullies and balances Altering

a large two centre lathe to be used occasionally as a collar [Mandrill

one for cutter etc] Turning

of cutters for cutting the planchets Making

of dyes in part of what is wanted Making

a drilling machine for the ingot moulds Making

lathe chucks for holding dyes and cutters Altering

a common iron flattening mill frame to be worked with [cogs] for coining

nearly finished Tools finished and in hand for the

other mints Sent to The

whole ironwork of a flatting mill complete A

large lathe with an assortment of tools etc 2

cutting machines made complete for cutting planchets Chucks

for holding the cutter In hand Three

cutting machines Two

frames for leveling the planchets |

||||||||||

References

4.1

4.1

4.10

4.10

4.11

4.11

4.18

4.18