The

Transitional Mints of the Deccan

|

Summary |

|

As the

British extended their control of India during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth

centuries, a number of areas that had active mints

fell under their management. Some of these mints were kept in operation for a number of years after they were taken over by the

British. Bhandare has used the term ‘transitional’ to describe mints of this

type [1], and

that convention has been used here, although the term ‘provincial’ is

sometimes used in the records. There are a number of

examples of this happening on the western side of India, where various

territories came under the control of the Bombay Presidency in the first half

of the nineteenth century. Pridmore has recorded the coins of some of these

mints (e.g. those of Sūrat), but, for some reason, he chose to

ignore others, even quite major mints such as Poona and Ahmedabad. Some

publications [2]

give listings of coins from these mints with headings such as ‘EIC’, but provide no supporting documentary evidence for the

attributions and these are sometimes incorrect. A study of the records stored

in the India Office Library has therefore been undertaken to fill some of

this gap. Inland from Bombay was the area known

as the Deccan, with the mints of Poona, Nasik/Chandore and Aḥmadnagar,

which were all acquired in 1817/1818. To the north lay the mints of

Sūrat, Aḥmadābād and Broach

and to the south were the mints of the “Southern Maratha Country”, Bagalkot

and Belgaum-Shahpur. Bankot, though not strictly a ‘transitional’ mint, is

included here because it behaved as a local mint. Bhakkar, in Sind, is also covered

in this chapter. The records are not completely clear about the operations of

these mints, but what archival evidence does exist can be combined with

knowledge of the coins themselves to produce a much clearer picture. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Circulatory context |

|

One important consideration in a

discussion of the transitional and local mints is the fact that the coins

issued from the mints that came under British control, together with those

that remained under the control of native rulers, circulated together with

many older types of coin in any one area. Local money-changers

or shroffs found a niche for themselves in exchanging one type of coin for

another at a rate that allowed them a profit. This rate of exchange is

referred to in the records as the “bazar” rate. Once the British had gained

control of the different regions, they instructed their local officials to

collect examples of all the coins circulating in these regions and send them

to Bombay for assay. The assay master at Bombay published two tables, one in

1817 [3]

(covering the Northern districts) and another in 1821 [4]

(covering the whole Presidency), establishing an official exchange rate

between all of the different coins in circulation,

allowing the local officials to accept the coins in payment of taxes. As the

grip of the British tightened on the territories in their possession, the

number of different coins that were acceptable in payment of taxes was

gradually reduced and hence the coinage gradually became more standard. However,

standardisation throughout the Bombay Presidency could not be achieved until

the mint at Bombay had acquired the capability of meeting the demand of the

entire Presidency and it could not do this until a new steam-driven mint was

introduced at the beginning of the 1830s. Even then, the coins of the

neighbouring states crossed into British controlled areas and continued to be

used by the local population. The old (pre-steam) mint at Bombay could not

meet the demand for the whole Presidency and this provides the explanation

for the existence of the transitional mints. They were essential in providing

sufficient currency until about 1834/35, because the Bombay mint could not

satisfy the demand, although many of the transitional mints were closed

before then. Coins in circulation in

the Bombay Presidency in 1820 are shown in the appendix at the end of this

section [5]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Aḥmad Shāh I, sovereign of

the independent state of Gujarāt, founded the city of Aḥmadābād

in AD 1411 and it became the capital. Akbar annexed Gujarāt in 1572/3

and from then on Aḥmadābād was an important mint town of the

Moghuls, the majority of the emperors having coins

struck there. Moghul rule continued

until the end of the reign of Aḥmad Shāh Bahādur. The city was

then taken by the Marathas who, in 1755, were

ejected by a Moghul army under Momin Khān, who restored the rule of the

emperor, at least nominally. In 1757 Momin Khān surrendered Aḥmadābād

to the Marathas, an event that ended all Moghul connection with the place.

Between 1757 and 1817 the city was either in the hands of the Marathas or

held on lease by the Gaikwars of Baroda. In 1817 an agreement was struck

between the Gaikwar and the British to hand over Aḥmadābād to

the latter. This was duly implemented and the

British took over the city including the mint [6]. However, the British had

been established in the city for many years before 1817. A Company of 32

Englishmen, led by Mr Aldworth had arrived at Aḥmadābād in

1613 and a house had been bought and a factory established in 1614 [7], but

they had not obtained any right to coin money. They were obliged, therefore,

to have their bullion coined at the local mint and several references exist

in the records concerning the problems that this caused (e.g.

the cost) [8]. After the British took control of the

city in 1817, the Collector, Mr. Dunlop, found the mint closed and the supply

of circulating medium so low as seriously to impede trade[9]. This is confirmed in a letter from Dunlop

to Government in which he proposed to abolish a nominal currency called “Aunt” (sometimes spelt Ant) and in which he explained the

background to the problem. He stated that in 1780/81 the mint had been closed

and sicca rupees had become scarce, so the merchants resorted to transfers in

each other’s books as a method of mutual payment. This was referred to as “dealing in aunt”. In 1805/06 this had

been prohibited and this prohibition had continued all the time that sicca

rupees were available. However, the mint had been closed again (no date

given) and dealing in “aunt” had

restarted and still continued in 1818 when Dunlop

wrote the letter [10]. Dunlop appears to have re-opened the mint in December

1817 [11]: In reference to your letter

of 20th February approving of my proceedings with respect to the Sicca mint

at this place, I have the honor to transmit for information of Government an

abstract statement of the sums coined, and showing also

the amount of profit, which has been brought to the credit of Government. The

system reported in my letter of 28th December was continued until the end of

February, when the receipt of your letter above referred to, directing me not

to seek a higher rate of profit than might be sufficient to cover all

expenses, determined me to fix the same rate of mint charges as that taken at

the mint in Bombay, namely three per cent, which is considerably cheaper than

the natives have been accustomed to get their bullion coined, so that the

small advantage which accrues to Government on this rate, did not appear more

than sufficient to cover incidental expenses, or more than should reasonably

be paid for coin to secure it from being melted up for common purposes. The

amounts allowed both for wastage or melting and forming the coins were found

by experience to be too large and have been accordingly reduced, but the

contractors for smelting, I have reason to believe, have gone rather too far,

and that some small increase to the present allowance will be requisite, the

bullion now melted at 3 rupees per thousand less than the rate formerly

reported to Government. Every

savings of this description is immediately carried to the credit of

Government, and the whole profit is up to the end of June amounting to Rupees

31421.1.82, and the mint continues to be supplied with bullion, so that there

does not appear any prospect of the working being stopped. It

seems only requisite for me to notice the large amount of profit which

appears during the first months, the Mint had not been worked before for a

considerable time, siccas had consequently obtained an artificial value, from

their scarcity, and bullion sold from this cause at a very low price, as

compared with sicca rupees. Several

other causes concurred to produce the same effect. Dollars have been imported

freely for inland speculations, which were all abruptly stopped by the war,

so that there was a great competition at that time to have them coined, as

the only means of saving the interest, or disposing of their commodity. Under

the circumstances of trouble and responsibility to which the coinage of

upwards of twelve lacs and a half of rupees, has subjected me, and the large

profit which has resulted from my superintendence, I have the honor to

request you will submit my claim to Government for remuneration. The

duties of Mint Master were long performed by the Collector at Surat, for which, I am informed, he

received a monthly salary, and I request that Government may be pleased to

grant me an allowance, either on this principle or such other as may appear

most advisable to the Right Honorable the Governor in Council. Details

of the amount of coin produced at the mint are also shown in this extract and

have been summarised in the following table:

Amount of Silver Coin Produced at Aḥmadābād In

February 1818, the mint committee in Bombay, whilst agreeing with Dunlop’s

actions in restarting the mint, suggested that the Judge and Magistrate (one

person) at Aḥmadābād should visit the mint two or three times

a month and indiscriminately take a few coins and send them for assay at

Bombay. Thenceforth this provided the means of controlling the quality of the

coins issued from the mint [12]: …As a means of placing

the mint however, as far as possible under the control of the mint officers

at the Presidency, in the same manner as the Surat mint formerly was, the Judge and Magistrate

should be instructed to proceed without any previous notice two or three

times in the month, at the least, to the mint and oftener when much business

is going on, and to take a few pieces indiscriminately from the hands of the

workmen – say not fewer than ten – and dispatch them under his seal at the

end of the month, to the Mint Master at the Presidency for examination. In

October 1818, the mint committee recommended that the coinage should continue

but the Financial Committee resolved that the Aḥmadābād

authorities should be asked for their opinion on the necessity for this,

given that a new uniform coinage (for the Bombay Presidency) would soon be

issued following the installation of a new mint at Bombay [13]. Of

course, the new Bombay mint did not actually become operational until the

1830s, when a steam driven mint started operations, but, in 1818,

consideration was being given to the possibility of building a local machine-driven

mint (see Dr Stewart’s pattern coins.). As far as the copper coinage was concerned, Dunlop found

that there was a shortage in 1818, but that this was caused by the shroffs

deliberately taking the coins out of circulation. He therefore immediately

began striking copper pice at the mint, with the effect that the hoarded

copper was released into the market and minting was stopped [14]: In reference to my letter of 6th May, I

request you will have the goodness to acquaint the Right Honorable the

Governor in Council that the shroffs of this place had so completely

engrossed all the former pice coinage, with the view of [forcing] the people

to accept of a much smaller number than had been fixed for the rupee, that no

change was to be obtained in the city. Finding it impossible to

ascertain the persons by whom this monopoly was made, it became necessary for

me immediately to coin other pice, for which purpose I purchased one hundred

maund of copper, on the best terms procurable (an account of which shall be

afterwards forwarded) and yesterday began making pice of the same weight as

those now current here, and I am happy to say with the very best effect, as

pice are today in sufficient numbers at every shop for the established rate

of 64 per rupee. The object I had in view

being thus answered I shall not carry the experiment any further at present,

than the quantity of copper already purchased (with the approbation of

Government) than may from time to time be necessary to defeat similar

interested combinations of shroffs. The

copper coinage of Aḥmadābād was discussed by Wiggins in 1981 [15]. He

believed that copper pice were only struck dated 1234 and 1236 and that those

given the date 1233 (1817/18), by Masters [16], were

the result of an incorrect reading because this date was too early for the

EIC. However the letter from Dunlop (above) would

seem to refute this and coins dated 1233 are included in the Stevens

catalogue [17]

(indeed Wiggins had one of these in his collection, so his view may have

changed after writing his paper). Pice dated 1232 and sold in the Noble sale

(Noble (1995), sale 48, lot 2170) must be pre-EIC or may be a mis-reading. Unfortunately, there were no photos of these

coins in the sale catalogue. Coins dated 1235 have been reported by Masters and in the Noble sale so this date is included in

the catalogue [18]. In 1819 the standard for the Aḥmadābād rupee

was established by the assay master at Bombay [19]: I am not aware that the professed

standard weight in troy grains or quantity of pure silver in the Aḥmadābād

sicca rupees has hitherto been declared,…; perhaps

the best standard would be weight 181 troy grains and purity or touch 85⅛

per cent. Each coin would thus contain 154 grains and a small fraction of no

importance, of pure silver. I suggest this standard because it is very nearly

the actual average of the coins of last year. There

are further references to the results of assays of the coins from the Aḥmadābād

mint in 1821 [20],

and in 1828 the Collector was able to report [21]: …there is no other coin current in

this collectorate except the Aḥmadābād sicca rupees which are

always received in revenue payments and struck by the Government at this

place. No

record of the date of final closure of the Aḥmadābād mint has

been traced. By 1832 the mint had stopped producing copper coins because a

proclamation was issued in that year concerning the rate of exchange of the

new Bombay quarter annas for the old Aḥmadābād pice [22]: The Right Honorable the

Governor in Council is pleased to give notice that the old pice called

Ahmadabad, being genuine coin and not counterfeits, shall continue until

further orders to be current throughout the several Purgannahs comprizing the

Ahmadabad collectorate and will at all times be exchangeable for the new

copper currency to the extent of the supply in the revenue treasuries of the

district and Sudder station at the rate noticed below. Sixty

new quarter anna pice for 68 Ahmadabad pice. Rupees and half rupees exist dated 1249 (1833/34) so the

mint cannot have been closed before then, and Masters [23] lists

coins dated 1250 and 1251 so the mint may have continued in operation until

1835, although no coins of these dates have been seen by the current author. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

There is no clear reference to the

site of a mint operating under British jurisdiction in Aḥmadnagar.

There was a Maratha mint at Wabgaon (Vaphgaon), which is close to Aḥmadnagar

[24], so

perhaps this mint was operational during the 1820s. In any case, an entry in

the records does suggest that a mint was operational [25].

Average

annual coinage for 10 years prior to 1833/34 at the Presidency and

subordinates. Alternatively, the table might simply refer

to coins supplied to the Nasik and Aḥmadnagar collectorates from the

Chandore mint. The design of the coins is not known. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

In 1820, consideration was given to a request

to establish a mint at Aḥmadnagar by Captain Gibbon [26]. The

mint was to produce coins for the whole Deccan with Captain Gibbon himself

acting as mint master. The coins were to consist of silver rupees (double,

single, half, quarter and eighth) and copper pice (double, single and half)

and specimens of the rupee and pice were sent to Bombay. In the event, the

proposal was rejected on the grounds that a serving officer could not

undertake such work and there were no plans to establish a mint master for

the Deccan. However, a specimen of a copper pattern rupee for the Deccan

dated 1820 exists in the Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay and was published

by P.L. Gupta [27].

There is a high likelihood that this is an example of the pattern rupee

submitted to Government by Gibbon. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bagalkot,

Belgaum, Shāhpūr and Dharwar Mints |

|

The British knew the area in the south

of the Bombay Presidency as the “Southern Mahratta Country”, which contained

mints such as Shāhpūr, Belgaum, Bagalkot and Dharwar that were

acquired in 1817/18. There are fewer references

to these mints in the records, particularly later in the 1820s, than there

are for some of the other mints and the analysis of those coins that were

produced, where and when, is therefore rather scant. The first reference to the mints in

what the records refer to as the “Southern Mahratta Country” occurs in 1820

when the commissioner for the Deccan referred to a problem encountered in

paying the troops with so many different types of coin in circulation. He

recommended that a new mint should be established to replace those at

Shāhpūr and Bagalkot [28]: I have the honor to submit together

with its enclosures, the copy of a correspondence with the Acting Principal

Collector and Political Agent in the Southern Mahratta Country which has

taken place in consequence of the complaints that have been preferred by the

troops of the losses sustained by them in the depreciation of the currency in

which they are paid. I have instructed Mr

Thackeray to make such immediate alteration to the rates at which coins are

paid into his treasury as may be most likely to check the fluctuation which

is experienced in the values of the currency, and I beg leave to submit to

the consideration of the Honorable the Govr in Council the arguments by that

Gentleman in favour of establishing a new mint, that may supersede the

coinage of the old ones at Buggrekotta and Sharpore. By 1821 some action had been taken on this proposal and a

new mint had been established at Belgaum [29]: I have the honor to

enclose for your inspection one of the first coins struck at the mint which

was lately transferred from Sholapoor [I presume that this is Shahpoor] to Belgam. The impression of the new coin differs from that of the

old only in bearing the date of the present currency, and the same weight and

proportion of alloy are still observed… The Commissioner was able to report to the Bombay

Government in May of 1821 [30]: I have the honor to

forward for the information of the Honble the Governor in Council, copy of

correspondence with Mr. Thackeray in regard to the

mints and coins in the Southern Maratha Country. In

concluding our final settlement with Chintamun Row, in which the

relinquishment of his mint at Shahpoor was an express condition, it became

necessary to consider the best means of supplying its place, particularly as

the Shahpoor rupee is also coined by the chief of Kittoor. I, in consequence,

suggested to Mr Thackeray to stop the mint at Kittoor as well as Shahpoor,

and instead of supplying their place by a new mint of the same coinage at

Belgaum, to abandon our own mint at Bagrekotta [= Bagalkot], and establish one new mint for the whole at Dharwar. The rupees of Bagalkot and Shahpur were well respected in

the area: As the Shapoor rupee is

at present to be coined at Belgaum, I trust that no great inconvenience will

be felt by the merchants who used to carry their bullion to Shapoor and

Kittoor. The management of the late Shapoor mint are far more respectable

than those of any other mint in the Dooab. They merely coin the silver that

is brought to the mint, without having any other concern in it, so that the

satisfaction that they give to the owners of the silver is the best test of

the integrity of the coin. This security and the rules which have been laid

down, will I hope, under a [regular] superintendence, prevent any abuse in

the new mint at Belgaum. In

my letter of the 7th October last, I endeavoured to

point out the evils to be apprehended from any sudden innovation with respect

to the mint. Further experience has convinced me that it would be inexpedient

to stop the coinage of either the Bagulkota or Shapoor rupee, until a

superior currency is ready to supply their places in the markets of the

Dooab. Much pains have been taken to prevent the

depreciation of these coins, and the very favourable rates at which they

exchange in remote and foreign bazars is the best proof of their intrinsic

value – in the bazar of Sholapur the local currency is far less acceptable

than the rupees of Shahpoor and Bagulkottah. If therefore we abolish these

coins, before they are superseded by the natural operation of a superior currency we shall only make a blank in the circulation,

which will be filled up by an inferior substitute. I

would therefore submit the expedient of continuing the coinage of the

Shahpoor and Sicca rupees at Belgaum and Bagulkotah. The idea of establishing a mint at Darwar, proposed

above, was discussed further in the same letter: With respect to the

expediency of re-establishing a mint at Dharwar, although Darwar itself is

not a place of much trade, its situation is central, it is near the large

trading town of new [Hoobly?], and it is the seat of an ancient mint. The

coin originally struck here was the Darwar Pagoda and as the revenue of the

adjacent Talooka were formerly collected exclusively in this coin, its value

was perhaps overrated. In Tipu’s time the Bahaduree Pagoda was struck at

Dharwar and the general currency of this coin both here and in Mysore would

make it far preferable to the Darwar Pagoda, if it

were thought advisable to re-establish a gold coinage. There

are indeed several considerations which would make it desirable to coin the

Bahaduree Pagodas at Darwar – it is money of account in many parts of the

district, it is more acceptable than any other coin in some of [the]

countries that trade with the Dooab and its parent mint in Mysore is said

[to] be losing its character for integrity. Much of the gold that supplies

the mint of Mysore is carried from Goa through the Dooab, and if there were a

mint to keep it here, a new channel of commerce would be opened between the

district and the coast. The situation of Darwar would also be more favourable

for a gold than a silver currency as the former is much more portable. For

these and other reasons, I think a mint for Bahaduree pagodas might be set up

at Darwar, and tried for one year. It could at any

time be stopped, it would be attended with little expense, and no

inconvenience that I am aware of, and until the experiment be tried, it is

difficult to judge whether it would be better to adopt the old gold coin of

the place or a new silver one. The

integrity of the coin will be best supported by the kind of security noticed

in the 2nd paragraph of this letter and if the coiners are prevented from

working on their own account it will be easy to check abuses in the mint… …To

check this evil I would propose that a proclamation

should be immediately published, excluding all coins from the revenues of the

ensuing Fasli, except the Madras pagodas and rupees; the Bahaduree or Ikeree

and Darwar pagodas, the Soortee or Bombay rupees, the Sicca or Bagulkotah,

and Belgaum (cidevant Shapoor) rupees. Objections may I know be made to this

measure but all that have struck me are counterbalanced by its advantages. The proposal to reduce the number of coins accepted into

the treasury was adopted almost immediately [31] and by

1823 the desired effect had been achieved [32]: Adverting to the state

of the currency, I beg leave to solicit the attention of the Honble the

Governor in Council to Mr Thackeray’s observations on the

subject of mints and to his former correspondence on this head, which

has been already laid before Government. It

appears that a great improvement has been brought about by the abolition of

the Kittoor and Moodhal mints and the transfer of that of Shapoor belonging

to Chintamun Row, to Belgam. The exclusion also of the inferior coins from

the collections, a measure which Mr Thackeray had judiciously adopted, has

had the good effect of silencing also the mints of Kolapore and of the

Jageers, and Mr Thackeray is of opinion that what is now chiefly wanted, is the

substitution of one uniform coinage for the currency of the Belgaum and

Baggrecotta [Bagalkot] mints. The Bagalkot mint is believed to have

closed about 1833 [33]. The earlier

proposal to establish a mint at Dharwar in the Doab appears to have been

accepted [34]: With regard to the proposal of establishing one regular

mint at Darwar for the whole of our possessions in the Southern Maratha

Country, we see no material objection to the measure, providing the several

cautions adverted to in the 3rd and 6th paras. of this report be kept in mind

and that the receipts are likely to cover the charges. and there is an entry referring to the

number of coins produced at Dharwar from 1823.

Average annual coinage

for 10 years prior to 1833/34 at the Presidency and subordinate [35]. This

seems to imply that coins were produced at Dharwar throughout the 1820s, at

least from 1823, until at least 1833/34 though exactly what coins were

produced there is not known. Presumably, They were

gold pagodas of some sort, as proposed by the commissioner in his letter

above |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Introduction Dholarah or Dholera is an old port

city, located in Dhandhuka Taluka of Aḥmadābād district in

the modern state of Gujarāt. Dholera’s commercial importance dates back to the 18th-19th

centuries. The creek on which it stands was then open to shipping, so it was

quite an important, though small, port on the Gulf of Khambhat (Cambay). This

part of the Kathiawar peninsula first came into the possession of the EIC in

1802 as a result of treaties signed with the leading

political powers in the region, namely the Gaikwads of Baroda and the head of

the Maratha Confederacy, the Peshwa. During the American civil war (1862-65),

Dholera emerged as the chief port for cotton export in Gujarāt,

supplying cotton from upcountry cotton-growing regions to Bombay. However, by

the end of the nineteenth century the port had silted up and was no longer

used. Attempts to revive it are under way. Archival

References: In 1816 the Collector of Kaira (Mr Rowles),

the district under which Dholera was jurisdictionally located, wrote to the

Governor in Council at Bombay informing him that there was a shortage of

copper coins in the area and asking to be allowed to re-establish a ‘pice

manufactory’[36]: I request you to

represent to the Right Honble the Governor in Council that the copper

currency within the Kaira Collectorship is extremely bad and that the lower

orders of society, whose labor is compensated by a daily payment in pice, are

considerable sufferers from this circumstance. In

addition to the badness of the pice, a further inconvenience is experienced

arising from the different degrees of value set upon them, and not only in

different towns and villages are pice of different weights and value in circulation,

but even in the same place. The

class of society that benefits from this want of uniformity in the copper

circulation are the many changers who speculate with the commodity, as a

merchant with any article of traffic, and thus obtain an advantage in

addition to what they are justly paid on exchanging copper for silver or vice

versa. The

copper currency in the districts subordinate to the Guicowar, the Peshwa, the

Nawab of Cambay and in fact throughout the province generally, with the

exception of this jurisdiction, is brought under control, either by the

establishment of manufacturies or by sanctioning such pice only to pass in

circulation as are of a certain weight, which is ascertained at an office

fixed for that purpose and the approval is notified by a stamp [the

countermarked coins of the area]. The

pice in circulation in this jurisdiction are chiefly manufactured at

Bhownugur by a class of people called Purjea Soonees, and

are of a very inferior description with regard to the metal they are composed

of, as well as their weight. Consequently they are

much cheaper than any other pice, and the poor person who may receive payment

by a given number of pice, instead of a certain proportion of a rupee is a

material sufferer from the depreciation. The

reason why no measure has hitherto been adopted to remedy this evil within

the Kaira jurisdiction, originates in a measure proposed by the Honble the

Court of Directors, communicated in their letter of the 7th

September 1808, and replied to by my predecessor on the 13th April

1809, when it was suggested that 50,000 rupees worth of pice of British

manufacture should be forwarded for the use of these districts, but the

suggestion has not since been adopted. Under

date the 25th August 1810, I had the

honor to submit a petition relative to the establishment of a pice

manufactory at Dollerah, to which the sanction of Government was communicated

on the 10th of the following month permitting me to make an

experiment of the plan proposed. The

manufactury was accordingly established and about four hundred and nineteen

maunds of copper were worked into pice and circulated at the proposed rate of

64 for a rupee. As

the experiment was only extended to Dollarah and its vicinity, this quantity

of pice proved sufficient for the circulation and I stopped the manufactory,

fearful that a more extensive issue might tend to detract from the value of

the pice and thereby not only be productive of a loss but also baffle that

part of the object which was to keep the exchange at a given number of pice

for a rupee of a given value. The

pice above stated to have been manufactured for Dollerah are now become

inadequate to the demand and it would be expedient to set the manufactory

again on foot, provided the objective is not extended and rendered applicable

to the whole of the jurisdiction. A

sense of the benefit that will accrue, both to Government and to the Public,

from the establishment of a regular pice manufactory, makes me solicitous to

submit the subject for the consideration of the Right Honble the Governor in

Council, and to request his sanction to the introduction of a manufactory at

this place for the use of the jurisdiction generally. The

Governor passed the request to the Bombay mint committee who replied that

they were not in favour of copper coins being produced anywhere in the

Presidency except in the Bombay mint but that they would like to have

specimens of all the copper coins in the district sent to them [37]: We have the honor to

acknowledge the receipt of your letter dated the 1st instant

giving cover to the copy of one from the collector of Kaira and desiring us

to suggest the most advisable means to be adopted for supplying the

collectorship of Kaira with copper pice. In

reply we request you will have the goodness to state to the Right Honble the

Governor in Council that in our opinion it is not desirable to sanction

private coinages of any description and that as all our other mints are now

abolished, not only the Kaira Collectorship, but all the districts

subordinate to this Presidency should in future be supplied with copper pice

from the Bombay mint. To

ascertain how this might be effected in the best manner, it was necessary

that we should inform ourselves of the actual value of what Mr Rowles

appeared to consider the best description of Pice in circulation in the Kaira

district and we have accordingly been endeavouring, but in vain, to trace any

account on our records of the expense or outturn of the four hundred and

nineteen (419) maunds of copper stated, in the eighth paragraph of that

gentleman’s letter, to have been coined into pice at the pice manufactury at

Dollera in 1810. Under

these circumstances we beg to recommend that the collector be directed to

send down by an early opportunity specimens to the number of sixty four (64)

of each sorts of the different kinds actually current within his district for

examination, and in the meantime, judging from the description Mr Rowles has

given of them, we may state that we have little doubt that a superior coinage

may be introduced of a weight sufficient to secure a regular supply from this

mint without incurring loss even in the event of the price of copper becoming

much higher than it is at present. A

copy of this was passed to the Collector at Kaira with instructions to send

examples of the copper coins in circulation there, to Bombay. In December of 1816, the assistant

collector of Kaira replied to the mint committee’s request and sent the

copper coins as ordered [38]: I have the honor in reply

to your letter dated 30th August last, with copy of a letter to

your address under date the 24th of that month from the mint committee,

on the subject of a coinage of pice for this jurisdiction, to transmit

specimens to the number of sixty four of each sort

of the different kinds of pice now current within this collectorship. I

beg leave to refer the Right Honble the Governor in Council for every

information which seems requisite in regard to these

specimens (ten in number) to the annexed memorandum. In

reference to the 3rd paragraph of the Committee’s letter to your

address, I have the honor to submit a statement exhibiting the result of the

manufacture of pice which Mr Rowles, in the 8th para of his letter

of the 9th July last, reported to have

been carried out at Dhollera, under the authority of Government dated 25th

August 1810. The quantity of copper coined did not exceed 330 maunds, 1

quarter, 1 pennyweight… In

the same letter he provided a list of the different types of pice sent to

Bombay: Bhaunagar, old Bhaunagar, new Goga* Dhundroka* Dollerah* Dholka Kaira Mondeh Nerriad Naupar He

stated that those marked with a * were of the Dolerah coinage of 1811 &

1812. They are place names, marked on the map as Dhandhuka and Gogo (as well

as Dholera). Exactly what this means is not entirely clear, but it will be

discussed further below. He also added a statement of the number of pice

produced: 330 maunds 11¼ [gr]

copper coined into pice at 64 per rupee, yielding 725,990. Value rupees 11,343 . 2 . 37 This

whole event provoked considerable discussion within the Bombay mint committee

about the necessity to improve the coinage of Bombay but as far as the Kaira

copper coinage was concerned, it was eventually decided that 50,000 rupees

worth of pice should be sent to Kaira from Bombay [39] and

no further pice coinage took place at Dholera. The

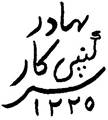

Coinage: Recently,

copper coins with mint-name ‘Bandar Dholarah’ were identified by Dr. S.

Bhandare. The coins are rather crudely struck specimens on which, as is

usual, only part of the legend can be seen. The date is rarely visible, but

specimens have been found with clear dates AH1225 and 1226, both of which

match exactly with the duration of the functioning of the ‘manufactory’ as

indicated in the archival reference reproduced above. The coins weigh about

8-9g and have a diameter of about 19.5-21.5mm. A full-die impression, showing

complete obverse and reverse dies, can be created:

The

obverse carries a Farsi/Hindustani inscription Sarkar Kampani Bahadur followed

by the date, and the reverse carries a legend Bandar Dholarah. Both

inscriptions are enclosed within circular borders – on some coins it is

composed of a saw-toothed inward edge. On one coin, the saw-teeth are

replaced with semicircles. There appears to be a difference in placement of

legends – on coins dated AH1225, the word ‘Bahadur’ appears at the top,

‘Kampani’ and ‘..kar’ in the word ‘Sarkar’ appear

below it and the date is placed right at the bottom of the design, beneath a

divider formed by ‘Sar…’ ‘Sarkar’. On coins dated AH1226, the word ‘Bahadur’

appears after the word ‘Sarkar’ and it seems the

word ‘Kampani’ forms the last horizontal divider at the bottom. Contrary to

the issues of the previous year, the date 1226 appears right at the top.

Depending on this variation, the coins may be classified as ‘Type 1’ and

‘Type 2’. There is also a noteworthy degradation

noticed in surviving specimens of both types. On some coins, the legends are

executed in retrograde, on others the words ‘Sarkar’, ‘Kampani’ etc. are

ill-executed, the ‘Ka’ looking more like the Indian numeral ‘4’. This

observation seems not in congruence with the fact that the ‘manufactory’ was

run for a relatively short time only as an ‘experiment’, and one would

presume the issue was not long enough lived to induce so many die-variations

and executional changes in the design. Another significant aspect to be noted

is that at least two of the known coins are overstrikes. The under-type in

one instance is a copper falūs, struck in the name of Muhammad Akbar II,

issued by the Maratha government mint at Ahmedabad. It is listed as T6 for

the Ahmedabad mint by Maheshwari & Wiggins[40]. It

is plausible that the second piece also has the same under-type, although it

is not as clear as it is in the first instance. This is interesting inasmuch as both coins have the ‘Dholarah’ overtype of

reasonably crude calligraphy. The under-type is listed by Maheshwari &

Wiggins as bearing RY9 and AH1232/RY10. It appears to have been struck during

a period of a temporary re-occupation of the city by the Peshwas after almost

ten years of control by the Gaikwads of Baroda (for further discussion on Aḥmadābād

coins, see Shailendra Bhandare - ‘Maratha Issues of Ahmedabad’, ONSNL 184,

2005 and Alfred Master – ‘The post-Mughal coins of Ahmedabad, or a Study in

mint-marks’, JASB-NS, vol. XXII, 1913). The fact that the under-type is dated

to AH1232 clearly indicates that the issue of ‘Dholarah’ coins, albeit of a

cruder execution, went on for at least seven years after the Company’s

‘manufactory’ situated there struck coins in AH1225 and 1226. These later

coins would fall into the category of ‘Katchha’ pice, as identified by Barry

Tabor [41], and

have been discussed in more detail by Bhandare & Stevens [42]. It

is possible that these coins were struck at one of the other mints mentioned

in the list above. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Around Bombay itself, and down the

coast, was the area known as the Concan which had a Northern and Southern

district, some of which came under British control as early as the

mid-eighteenth century, but mostly fell under their control after about 1817. The British are not known to have

produced any coins in the Northern Concan and this area will not be discussed

further. However, this is not true of the area known to the British, in the

early nineteenth century, as the Southern Concan. This district lay on the

west coast of India to the south of Bombay (Mumbai). Bankot, with its fort

and nine surrounding villages, had been ceded to the British by the Peshwa in

1755 and 1756 but it was not until 1819, following the final Mahratta war and

the acquisition of further territory, that the area was formed into the

separate collectorate of the Southern Concan. Initially Bankot, which was

also known as Fort Victoria, was the headquarters of the collectorate but in

1820 this was transferred further south to Ratnagiri, and in 1830 the three

subdivisions to the north of Bankot Creek were transferred to the Northern

Concan collectorate and the Southern Concan was reduced to the rank of

sub-collectorate. This situation only lasted for two years and in 1832 the

Southern Concan was again raised to the status of collectorate[43]. The

Southern Concan was also known as Ratnagiri after the place of its

headquarters. The currency of the Concan

was mixed, the brisk sea trade bringing into the district every sort of

Indian coin. Up until 1835, the main coin was the Chinchoree rupee (struck at

Poona), and later the Surat rupee (struck at Surat and Bombay),

supplemented by various older rupees known as Chanvad, Doulatabad, Hukeri,

Chikodi and the Emperor Akbar’s Chavkoni, or square rupee. After 1835, the

Company’s rupee gradually superseded this heterogeneous currency until, by

1880, the Imperial currency was the sole circulating monetary medium [44]. Following the creation of the collectorate

in 1819, a copper coinage was issued to meet the needs of local tradespeople

and Pridmore catalogued the coins[45]. They

are crudely struck, consisting of three denominations: double pice, pice and

half pice, and variously dated 1820 and 1821. Similar coins dated 1828 and

1829 will be dealt with in the section on the Rahimatpur mint. The

Coins and their Use On the 30th

June 1820, Mr. Pelly, the collector responsible for the Southern Concan,

wrote to the Governor and Council of the Bombay Presidency stating that the

people of the area were suffering considerable inconvenience because of the

lack of copper coins available for everyday commerce. He believed that this

was caused because the copper coins were exported more profitably for their

metal content rather than being exchanged for rupees. He had tried to

intervene by sending pice from areas where there were fewer difficulties, to

those where the problem was most acute, but this had not succeeded. He

therefore proposed that a copper coinage should be undertaken, either locally

or in Bombay, consisting of pice and half pice exchangeable at the rate of 64

and 128 to the rupee respectively. Pelly’s proposal was referred to the mint

committee who agreed that it seemed sensible, given the circumstances, and

recommended that the contract for striking the coins should be open to

competition and that, before authorising the coinage, the collector should

send specimens to Bombay for examination [46]: I beg leave to represent for the

information of the Honble the Governor in Council that for some months past

considerable inconvenience has been experienced in this Zillah owing to a

scarcity of copper coin, which has been withdrawn from circulation

principally owing to the course of exchanges having rendered its exportation

the most profitable remittance that could be made, to other quarters – at

Malwar when the fixed quantity of copper exchangeable for a rupee was

largest, the inconvenience has naturally been most severely felt. I have

endeavoured to lessen it, by sending thither supplies of pice from other

Tallookas – but this expedient if long pursued would obviously be merely

shifting, not removing the evil. What appears to be required [is] the issue

of a sufficient supply (perhaps half a lack) of this circulating medium, at

such a rate as may stop its exportation. And I would respectfully suggest

that a coinage of copper pice of 64, and half pice of 128, to the rupee, be

undertaken for this Zillah, either here or at Bombay – I venture to recommend

the half pice, because the inferior classes of inhabitants who are the

greatest consumers of trifling retail articles, are always sure to suffer by

the lowest denomination of coin in a Country, being of comparatively high

value, since scarcely anything they buy is charged lower than the smallest

current coin – and probably would not be charged much higher, even if its

intrinsic value were far less. The numbers have been selected from the

convenience they afford of each of them dividing by the annas in a rupee,

without a remainder – they possess moreover this further advantage, that as

the pice now commonly current are not generally widely different from this

same standard value, inconvenience from the introduction of the proposed new

pice is not, I think, to be apprehended. Ordered that a copy of

the preceding letter be transmitted to the Mint Committee with directions to

offer their opinion on the suggestions offered by Mr. Pelly for relieving the

scarcity of copper coin in the Southern Concan. The mint committee responded [47]: We have the honor to acknowledge the

receipt of your letter of the 11th instant, referring to us one

from the Collector in the Southern Concan dated the 30th ultimo

and desiring our opinion on the suggestion offered by Mr Pelly for relieving

the scarcity of copper coin in that district. In

reply we request you will do us the favour to state to the Honble the

Governor in Council that under the circumstances stated by the Collector, we

are not aware of any better mode of supplying the deficiency than by adopting

Mr Pelly’s suggestion of undertaking, or rather authorizing, a coinage of

copper, to a certain extent, on the spot. The rules we would

recommend would be the same as for the Broach copper coinage, namely that the

division should, as Mr Pelly proposes be 64 whole, or 128 half, pice per

rupee, and the privilege of coining should be assigned to a sort of

competition to the person who may be willing to coin the heaviest pice to be

exchanged at that rate, but without requiring any share in the profits. Before, however, finally authorizing the coinage, it might

be advisable that a few specimens of the proposed coin should be forwarded to

the Presidency for examination. Ordered that instruction

be issued to the Collector in the Southern Concan to invite proposals for

coining copper pice comformably to the Mint Committee’s suggestions. Accordingly, in September 1820, Pelly

advised the Bombay Government that he had issued an advertisement inviting

tenders for making the new copper coins but that he had received only one

reply, from Sootoophoo Din Purkar, who had recommended that 25,000

rupees-worth of each of three denominations should be struck [48]: Pursuant to the instructions conveyed

in Mr Farish’s letter dated the 21st July last, advertisement (as

per accompanying translation) were issued, inviting tenders for coining

copper pice to the extent of seventy five thousand rupees which will probably

be required, the population of this zillah amounting to nearly six and half

lacks of person; and the export of copper pice being a common mode of

remittance by sea during the fair season. Of the only tender which

has been received in consequence of the above notification, I enclose a copy

on its merits. With reference to the Bombay currency, I am not able to offer

any decisive opinion, because I do not know the standard weight of copper,

which there ought to be in each Bombay Rupees worth of Bombay pice. Those

pice are not current here but having collected 50, and weighed them, I found

they fluctuated from about 41 to 42½ tolas of copper for a Bombay rupee – the

present tender offers a weight of 41 tolas of pure copper per Chinchoree

rupee, a coin rupees 3..2..52 percent inferior to

the Bombay rupee. I enclose, as desired,

specimens of the proposed coin. They seem, I think, better executed than the

Bombay coin. Besides the pice and half pice, I would recommend to be coined

about twenty five thousand rupees worth of the double pice, or half anna, as

per specimen no. 3, which will be a great convenience and in no way

objectionable that I can perceive, since, like the pice and half pice, a

rupee worth of them may be divided by the annas in a rupee, without a

remainder. The contractor, it will

be observed, expects that the copper (which is a British staple), should be

allowed to be imported into this zillah free of customs. The Honble the

Governor in Council can best determine whether this can be complied with; any

abuse of the privilege (if conceded) might easily be guarded against by

giving the contractor dustucks for the exact weight of copper necessary for

the fulfilment of the contract and no more. The security offered is wholly

unexceptionable. The contractor will probably solicit an advance of 20 or

25,000 rupees. PS Specimens of three

kinds of coin are enclosed as follows: No. 1 double pice or

half anna, 32 to the Chinchour rupee. No. 2 whole pice, 64 to

the Chinchoree rupee No. 3 half pice, 128 to

the Chinchoree rupee Sootoophoo Din Purkar’s offer was as

follows [49]: Your Honor having made notification

that sealed tenders will be received in Southern Konkan Collector’s Sudder

Kutcherry for the coinage of copper pice on the 26th day of August

1820 to the amount of seventy five thousand rupees in the proportions of one

third whole, one third half and the remaining third double pice, the whole

pice to contain sixty four and the half pice one hundred and twenty eight and

the double pice thirty two for each Ankosee Chinchoree rupee. I wishing to have

undertake the coinage of the seventy five thousand

rupees in copper pice and tender to your honor the weight of copper for each

rupee as follows Vizt: for every Ankosee Chinchoree rupee received

I engage to deliver forty one tola of copper in pice, or in English weight,

seventeen ounces one quarter Avoirdupois, the half and double pice to weigh

the same for each rupee. I have accompanying this tender sent muster of the different sizes

of the coin in whole, half and double pice as I perceived was ordered in your

Honor’s notice. I mention my friends

Abdull Guffoor and Dayen Khaun, they having agreed

to become security for my due performance according to agreement. I also wish to make

remark your Honor, this pice exceeds the Bombay average and I hope equally so

in other respects as to execution etc. I beg to mention to your

Honor that I make so much weight in my tender because I hope and conclude

your Honor not expect customs for the copper employed in this business, upon

importation here. Ordered that copies of the preceding papers together with the

specimens of the copper coin accompanying them be referred to the Mint

Committee. The three proposed denominations were

double pice, single pice and half pice, specimens of which were sent to

Bombay, via Pelly, as had been requested by the mint committee. The original

advertisement called for denominations of pice and half pice, and it is clear that the addition of the double pice denomination

originated with Sootoophoo Din Purkar, although Pelly subsequently supported

it. A translation of the

actual advertisement appears in the records as follows [50]: Notice is hereby given That at noon on the

twenty sixth day of August, corresponding with Suravan sood 3rd

Shalewan 1742 and 16th Zilkand 1235 Hejree, sealed tenders will be

received at the Southern Konkan Collector’s Sudder Cutcherree, for the

coining of copper pice. The coins must be rendered in whole or

half pice, the former consisting of sixty four (64)

the latter one hundred and twenty eight pice (128), to the rupee. A specimen of each kind

of coin must accompany the tender, and the contractor must give in the names

of two sufficient sureties for the due performance of this engagement. The tender must contain in words,

written at length, the weight of copper in Bombay seers, which the proposer

will undertake to deliver for each Ankoosee Chinchoree rupee, at sixty four whole, and one hundred and twenty eight half

pice to the rupee. The tender offering the

greatest weight (if in other respects approved of) will be accepted; and the

whole profit of the transaction will be the contractors. The contractor will be required

to deliver at least one thousand rupees worth of copper pice per week in the

proportion of half in whole, and half in half pice; to undertake to coin in

the whole to the value of seventy five thousand

rupees, 37,500 in half and the same quantity in whole pice, and he must

desist from coining when that quantity shall have been completed. The pice must be made of

pure copper, and not mixed with any other material; each pice, and half pice

cast, must be of uniform weights, should there be found any differences in

weight, the contractor will be punished. The mint committee was very

complimentary about the process that Pelly had used to get the proposal from

Sootoophoo Din Purkar and they considered the terms as advantageous to the community as could

be wished or expected. The quality of the copper and the workmanship in

the specimens submitted to the committee will

do great credit to the individual undertaking the coinage,

if the whole shall be completed in the same style. To ensure that

future coins were of the same standard, Pelly was asked to send specimens,

regularly, to Bombay for assay [51]. Sootoophoo Din Purkar had

signed the contract by November 1820, and Pelly requested permission to

advance him 25,000 rupees so that he could begin work on the first batch of

coins [52]. Adverting to the 5th

paragraph of my letter dated the 4th September last, and yours of

the 2nd ultimo, I beg to report that the contractor for the

coinage of copper pice for the use of this zillah, having executed his deed

of agreement under proper security, I request authority to advance him the

sum of twenty five thousand rupees, as mentioned at the conclusion of the

paragraph above referred to. Ordered that Mr Pelly be

authorized to issue to the contractor for the coinage of copper pice for the

use of his zillah an advance of rupees 25,000. By early May of 1821 he had produced

about 20,000 rupees worth of the pice and permission to start issuing the

coins was sought and received [53]. With reference to your

letter of 20th July and 2nd October last relative to

the new copper coinage in this zillah, I have now the honor to report that

the contractor has delivered upwards of twenty thousand rupees worth of pice

into the treasury at this station, and as great inconvenience has for a considerable

time past been felt throughout the different districts in the Southern

Concan, from the scarcity of copper coin, I beg to solicit the permission of

the Honble the Governor in Council to issue the quantity already received at

the rate of sixty four pice, or one hundred and twenty eight half pice, per

rupee. Ordered

that Mr Burnett be authorized to issue the copper pice received from the

contractor at the rate of sixty four pice or one

hundred and twenty eight half pice [per] rupee, of which the Mint Committee

is to be informed. In that month he was advanced another

25,000 rupees for the next batch of pice and the final 25,000 rupees in early

November 1821 [54]. I have the honor to

report for the information of Government that the contractor for the coining

of pice in this zillah has delivered copper coin to the amount of the sum

advanced to him agreeably to the orders conveyed in your letter of the 28th

November last and now beg to request the permission of the Honble the

Governor in Council to make a further advance of twenty five thousand rupees

on account of this contract. Ordered

that Mr Burnett be authorized to advance the sum of twenty

five thousand rupees to the contractor for the coinage of pice on

account of this contract. In November 1821, Sootoophoo Din

Purkar asked for another contract for a further 50,000 rupees-worth of pice

on the grounds that he had all the people and tools necessary to undertake

the coinage, which meant that it would be cheaper to strike another batch

immediately, rather than have to start again [55]. Petition of Sootfooteen

Purkar to J.J. Sparrow, dated 10th November 1821. Represents

that my present contract for coining copper pices nearly completed and I hope

to your satisfaction, I therefore offer, if you are desirous of coining more

copper pice to undertake the same on the terms of my present contract,

because I have at present workpeople and mint implements, and if the former

are once dispersed they cannot without great trouble be collected together,

in which case I should not be able to undertake the contract at the present

low rates. I therefore pray that you will take this petition into your

serious consideration and issue such orders as you may deem proper. However, the Accountant General had

noticed the final advance of 25,000 rupees and drew the attention of the

Bombay Government to the fact that no specimens of the new coinage had been

received at Bombay for examination since the original specimens sent before

the contract had been agreed [56]. With reference to your

letter of the 6th instant, apprizing me of a further advance

having been authorised to be made to the contractor for coining pice in the

Southern Concan, to the extent of twenty five thousand (25,000) rupees, and

having ascertained from the Assay Master that no further specimens of the

pice have been transmitted to the mint officer at the Presidency for

examination since those received with your letter of the 15th of

September 1820, to the address of the Mint Committee, I beg recommend that

the attention of the Collector be called to this very important point in the

orders conveyed to him on the 2nd of the following month. Resolved

that the corresponding orders be issued to the Collector in the Southern

Concan. Following this, the mint committee

examined specimens in January 1822 and they reported

that the quality of the coins was not equal to that of the specimens sent in

September 1820, although they had to admit that the assay master was away,

and that this was merely their opinion. However, they felt strongly enough to

recommend that the coinage should be stopped and no further pice should be

issued. The Bombay Government instructed the Collector to stop issuing the

coins, but not to stop making more [57]. In May 1822 a further ten

specimens were sent to Bombay and were again found to be of lower quality

than the first samples and to be of slightly lower weight. This time the

collector was instructed to stop the production of the coins and to report

how many had already been struck [58]. I am directed by the

Honorable the Governor in Council to acknowledge the receipt of your letter

dated the 19th ultimo and to inform you that the ten specimens of

the half pice of the new copper coinage accompanying it are found on

examination not to be so well executed [as] former samples transmitted to

Government nor to be of the full weight. They are a grain lighter than those

received in February last. The

Honorable the Governor in Council thinks it expedient to direct you to

suspend the further coinage of copper coins contracted for by Sootoophoodeen

Purkar and to report the value of those already struck by the contractor. You

will also be pleased to send up a number taken promiscuously of the different

coins made under the contract for further examination by the Assay Master.

The Mint Committee have been directed to suggest the number they may consider

sufficient for this purpose. He replied that of the original

planned 75,000 rupees-worth, 70,897 rupees, 2 quarters and 44 reas worth had

then been received into the treasury and that the greater proportion of the

outstanding amount had already been struck and was awaiting delivery.

Sootoophoo Din Purkar sent a petition to the collector for transmission to

Bombay, in which he tried to explain why the coins were of lower quality than

the original specimens and requesting that he should be allowed to complete

the contract, which he was allowed to do [59]. However, getting the coins

into circulation was not proving easy. In December 1821, the commander in

chief of the Bombay Presidency raised the matter of the troops in the

Southern Concan losing as much as a quarter of their pay because they were

being forced to receive part of it in the

Bankote pice. The exchange rate of 128 new pice per rupee (this must

refer to the half pice denomination) compared unfavourably to the old

exchange rate of 160 old pice per rupee, and the use of the new pice to pay

the troops was stopped. This incident does reveal the fact that the new

copper pice were struck in a mint established at Bankot. This is evident not

only from the above quote but also a reference to the new copper currency issued from Bancote in the same series of

correspondence [60]. By 1823 it had become

obvious that it would be impossible to get more than a small part of the 75,000

rupees-worth of pice into circulation in the collectorate within a reasonable

timeframe. The new collector in the Southern Concan, Mr Dunlop, gave serious

consideration to various possible options. Firstly, he thought about reducing

the value of the pice so that the number per rupee was increased from 64.

This was rejected on the grounds that, once started, the value would continue

to decrease until it reached the value of the intrinsic copper content, at

which point the pice would be sold for scrap metal and the whole raison d’être for issuing them would

be lost. In addition the reduction in value would

cause a considerable financial loss to Government. The second option was to

keep the pice in the treasury for a number of years

and release them slowly, at the authorised Government rate of 64 per rupee,

as the community needed them. This would also confer a financial loss on the

Government[61].

However, this second option seems to have been adopted almost by default, and

there was a very slow release of the coins into circulation over the next few

years. Fortunately, in 1824, the

Judge at Sūrat had another idea. For some time there had been a shortage of copper coins in

Sūrat and the Judge suggested that some of the surplus coins in Bankot,

in fact 10,000 rupees-worth, could be used to fill the gap [62]. As

soon as the Sūrat shroffs heard about this proposal they issued a

petition stating that they had plenty of copper pice and could meet the

requirements themselves if only the Government would allow them to over-stamp

the coins with the Company’s mark [63]. The

British authorities did not trust the local shroffs and this petition was

rejected [64]: …that

after a deliberate review of all the circumstances of the case, we are of the

opinion that the native community of Surat cannot be in such great want of an addition

to their copper currency as the money changers would wish us to believe and

that it seems pretty plain that the object of the latter, in wishing to

obtain the Government stamp on the pice in their possession, is to force a

spurious coinage on the public at a rate above its marketable value. That the copper circulation of Surat stands in need of a reform in common with

that of every subordinate district, we do not in the least doubt, but

conceive it would be idle, with the prospect of our efficient mint before us [this is a reference to the new

steam-driven mint to be built at Bombay],

to make the attempt with our present means, nor do we think it would tend to

any good end, to allow of any further coinages of copper being undertaken,

under the sanction of Government, as a private speculation. We

incline therefore to recommend, that the copper currency of Surat be left for the present as it is, that is,

the old pice passing as heretofore, at their marketable value, and the

circulation of the new (Concan) pice being under the proclamation which we

presume has been issued, entirely optional, which will afford at least some sort

of security to the lower classes against a worse currency being imposed on

them, until we shall be able to supply them with an entire new coinage which

cannot be imitated without machinery. Ten thousand rupees-worth

of Concan pice were shipped to Sūrat via Bombay, and a further 5,000 to Broach,

which was also very short of copper coin. In fact

the collector at Broach had already agreed a contract with local moneyers to

strike 7,000 rupees-worth of pice, but was instructed to stop this, if possible,

and wait for the Concan pice to arrive[65]. The

pice were to be exchanged at 64 to the rupee, but the Sūrat shroffs

refused to trade in the coins at that rate, and the experiment was not

successful there [66].

However, in Broach there was no such resistance and the coins quickly gained

acceptance [67].

In 1826, the shortage of

copper coins in Sūrat was felt even more acutely, and the judge

asked that the collector be given permission to strike copper coins locally [68].

However, the Bombay Government would not accept the proposition that the

Bankot pice could not be used, basing their conclusion on the fact that they

had been successfully adopted in Broach in 1824 [69].

They, therefore, sent a further 10,000 rupees-worth of the Bankot pice

together with a proclamation declaring that they would be issued at 64 to the

rupee and would be accepted back at the treasury at 64 to the rupee. A

further 5,000 rupees-worth was also sent to Broach [70]. This time the pice were

accepted and the following year, 1827, a further 20,000 rupees-worth were

requested although the records are not clear about whether

or not they were actually sent [71]. A

petition from the Sūrat shopkeepers of 1828 implies that they were

not [72]. What

is certain is that 5,000 rupees more were sent to Broach in 1827 [73],

making a total of at least 35,000 rupees-worth that were sent to Sūrat and

Broach (and possibly 55,000), of the original 75,000 that were produced. This exhausted the stocks

of the pice in the treasury of the Southern Concan, and when further demands

were made in 1828, the collectors at both Broach and Sūrat were instructed to strike pice locally,

though exactly what type these would have been is

not known [74]. In 1831, a certain

Nathooset bin Abaset sent a petition to Bombay asking for permission to open

a copper mint at Penn in the Southern Concan. This petition was passed to the

collector in the Southern Concan and he was asked

for his opinion. He confirmed that all of the

1820/21 pice were now in circulation and that there was a need for more

copper coins. Having spoken to Nathooset bin Abaset, he was able to confirm

that the petitioner wanted to produce 50,000 rupees-worth of pice [75]: …half

to be of the description coined at Bankote by Mr George Pelly in 1820/21 at the

rate of (64) sixty four per rupee, and half,

Doodandees, or old Poona pice, at the rate of (60) sixty per rupee, weighing

57 [per] Chinchoree rupee. Following this petition and its

rejection, the whole focus of the mint committee fell on the new copper

quarter annas (pice) produced in the new steam-driven mint supplied to Bombay

by Boulton & Watt of Soho, Birmingham, England. Because of the great

shortage of copper coins throughout the Presidency, the new mint concentrated

first on meeting this need as opposed to the silver coinage. Once the mint

was up and running so that the coins could be produced in sufficient numbers,

a difficult enough process in itself (see chapter 5

and also [76]),

it soon became clear that getting the coins into circulation was going to be

yet another challenge. At first the coins were simply sent to the different

collectorates throughout the Presidency in the expectation that they could be

exchanged for the old pice when these came into the treasury. However, the

rate of exchange of 64 quarter-annas for one rupee, inhibited this to such an

extent that, for instance, in Bombay itself there was little or no demand for

the new coins, with less than 50 rupees-worth having been issued by November

1831 [77]. A new

approach was taken in 1833 [78], the

intention being to target the collectorates one by one and offer favourable

terms of exchange for a short period to get the new coins accepted. The

Northern Concan was chosen as the first place for this new approach, which

proved to be successful, and, in 1834, the second collectorate to receive the

new coins was the Southern Concan, by then referred to as Ratnagiri [79]. This

approach again proved successful. Henceforth, the copper coinage for the

Southern Concan would be the uniform coinage of the Bombay Presidency

eventually replaced in 1844 by the uniform copper coinage for all of British India. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

The province of Sind was conquered and

annexed to British India in 1843 by Major-General Sir Charles Napier, whose

reputed telegram ‘Peccavi’ (Latin

for ‘I have sinned’ i.e. Sind) was in fact a caption

given to his picture by Punch magazine. No entries in the records,

referring to the Bhakkar mint, have been found, so the evidence at present

relies mainly on the coins. The mint at Bhakkar, which had been a Moghul

mint, then Durrānī and then local mirs for many years, continued to

issue coins and therefore falls into the category of a transitional mint from

1843 onwards. One type shows a lion, which is believed to represent the fact

that the British had taken control, but the longest-lived type has a

selection of floral ornaments amongst the Persian inscription. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

The port of Broach (Bharuch) on the river Narmada is a

town of great antiquity and was an important centre of trade and commerce for

a considerable time until superseded in importance by Sūrat. Broach was never a mint of the

Moghul emperors. In the eighteenth century it was part of the private estate

of the Governor of Gujarāt. A mint was established at

Broach during the time of the second Nawāb, Nek ‘Ālam Khān II,

by permission of the emperor, Aḥmad Shāh Bahādur (1748-1754).

In 1772 the Nawāb of Broach was deposed by the East India Company, whose

army took the city, the belief being that the Nawāb was in alliance with

the Gaikwars, who had designs on the Company’s territory. In 1782, by virtue of the

treaty of Salbye, the Company made over the port of Broach to Sindhia of

Gwāliār. Jambusar, a few miles to

the north of Broach, was occupied by the British from 1775 to 1783 and

contained a mint that issued coins during this time [80]. Coins struck at Broach

between 1772 (AH 1186) and 1782 (1197) fall into the British series but later

coins, up until 1803, belong to the Marathas [81].

Coins may have been issued from the mint at Jambusar during the time it was

occupied by the British but whether or not they were

also issued from a mint in Broach, itself, is not clear. In 1803, after the treaty

of Bassein, Broach once again became a possession of the EIC, who did strike

coins there at this time. Silver Coins A rupee dated AH 1173 issued in the

name of Ālamgīr II, regnal year 6, is known. However, no direct

reference to mints operating in Broach under the British, during the period

1772-1782, has been found in the EIC records and no coins are known. However,

there is a tangential reference in a record dated 1781 [82]: The

President acquainted the Board that there is a quantity of private silver on

the island [Bombay] brought by the freight ships from the

Gulf of Mocha and that it would be of the highest benefit to the place if

such an advantage could be held out to the proprietors as would induce them

to continue their bullion upon the island & convert it into Bombay

currency, otherwise that they will as usual export it to Surat and Broach where it will yield a larger

return from the mints. Although Jambusar features quite often

in the EIC records, there is no mention of a mint operating. However, rupees

have been reported with this mint name and dated RY 22 (1780/81) [83]. Kulkarni

pointed out that this date could be fictitious and that the coin might be a

Mahratta coin of a different time. The coins have a distinctive symbol in the

seen of julūs on the reverse [84]. In 1803,

the Company took over the mint at Broach and continued striking rupees and

fractions (halves and possibly quarters) and copper coins. The coins formerly

struck by the Nawābs had a flower as the predominant mark

but the Company changed this to the cross of St. Thomas. Although the mark is

often present on the coins, very few will be found with clear regnal years as

they are almost always off the flan. In a

letter to the Bombay Government dated 31st October 1814, the

Collector reported the value of rupees produced at Broach for each year from

1787 to 1803 under the control of Sindhia and then the value of those

produced each year under British control [85].

This seems to clearly establish the years in which silver coins were produced

at the Broach mint under EIC control with the silver mint being closed in

1814. A petition from local people to issue more silver rupees in 1820 was

rejected by Government [86].

Mintage

of silver coins at the Broach mint, 1803-1809

Copper

Coins In 1820 a decision was taken to produce copper coins at

Broach and to fix the exchange rate of pice at 64 to the rupee [87]. By

April of 1820 the Collector at Broach was able to report that he had received

a response to his advertisement for a contract for a copper coinage and he

sent examples of the pice to Bombay for examination by the Bombay Government [88]. The

assay master at Bombay reported that the coins weighed 139 grains 15 dwt each

and their manufacture was ‘wretched in

the extreme’ [89]. The

Collector at Broach was ordered to stop their production immediately. However,

in 1821 the Broach authorities were informed that they could restart the

coinage of copper provided that the quality of coins was improved [90]. In 1824 a contract for the production