The Ranas of Gohad and their occupations of

Brief history.

During the period of the decline and disintegration of the Mughal

Empire, which began towards the end of the reign of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb

Alamgir, in the last 20 years or so of the 17th century, many smaller

polities declared their independence, and a number rose to prominence. Of these, some remained local but a few began

to dominate large areas of the disintegrating empire. Among these rising powers were the Jats of

Bharatpur.

Under Raja Suraj Mal (1756 - 1763 AD., AH. 1170 - 1177) the power of the Jat confederacy reached its zenith, and he was arguably the strongest

ruler in

Rana Bhim Singh of Gohad

(1707 to 1755 AD.) was a subordinate ally of Suraj Mal, but had previously been a powerful

ruler in his own right. In 1740 AD., he had attacked the Gwalior Fort, which 'Ali Khan, its Mughal Governor, had surrendered without much resistance. For some years, Bhim Singh held

Thereafter, the fortress remained in the ownership of the Marathas in the person

of the said Vitthal Shivadeo Winchurkar until after the fateful Battle of Panipat,

in 1761 AD, (2) and the Jat resurgence described above. In 1763, Suraj Mal was

killed in an action against the Imperial forces, not far from

A. B. C.

Fig. 1. A: Chhatri in memory of Rana Bhim Singh near Bhimtal, in the Gwalior Fort. B: Portrait of Chhatar Singh. and C:

A

view of Gohad Fort. (Courtesy Wikipedia, ‘Jatland’,

L R Burdak) (2)

At the Battle of Panipat, the growing power of the Maratha confederacy received a crushing defeat at the hands of the massive invading Afghan army of Ahmad Shah Abdali (Durrani) and his Indian, mostly Pathan allies. The surviving Maratha troops and their leaders retreated in disarray, fled the field under hot pursuit and, with almost every man’s hand against them had to ‘run the gauntlet’ of hostile tribesmen, ryots and landholders throughout most of their return journeys to their Deccani homeland (3).

For

years, the Maratha Sardars had ruled much of the

As

a result, some of those polities that had been under subjection or tributary to

the Marathas and Mughals became restless and took advantage of the discomfiture

of their erstwhile suzerains. Some

rebelled, or attacked other former Maratha and Imperial possessions, now vulnerable. Among the rebels was Chhatar Singh, the Jat

Rana of Gohad, who, unlike his predecessors, was reduced

to the level of a local ruler whom Malleson described as a mere ‘Zamindar or

landholder’, and whose estate apparently consisted of a village and some

territory, formerly under Maratha suzerainty.

Shortly “after Panipat, he [threw off allegiance to the Marathas,] proclaimed

himself ‘Rana of Gohad’ and seized

Gwalior Fort [in 1761 AD.].” The conquest of Gwalior Fort by the Jat Rana of Gohad

is also confirmed by Dr. Ajay Kumar Agnihotri in his

Hindi ‘Gohad ke

jaton ka Itihas’ p. 29 (v). This conquest, though undoubtedly spectacular,

proved relatively short-lived, and the fortress was retaken in 1767 AD, (AH. 1181)

by Mahadji Sindhia, after Raghunath Rao, a man of ability - both soldier and statesman, who would later

become the Maratha Peshwa - had failed

in the attempt (6) . Thereafter, Gwalior Fort remained in Sindhia’s

possession until

Before

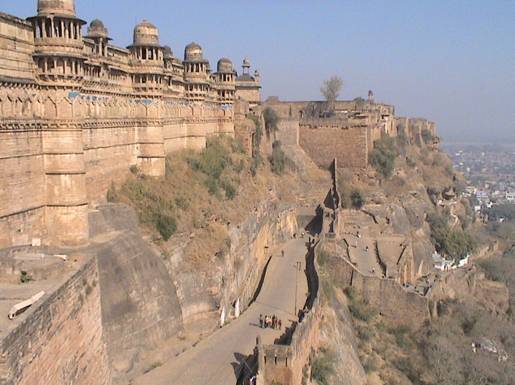

Gwalior

Fort (Figs. 1 and 2 below), atop the 300 foot high, steep sided Gopachal Hill, was reputed to be among the most formidable

in all India. It was famously described as “the pearl in the necklace of the castles of Hind,” (Taj-ul-Ma’asir), but because of its massive size it was, like Chitor, Ranthambore, Kumbalgarh, Rothas and others of its ilk, almost impossible to defend without large numbers of troops, certainly in the tens of

thousands, effectively to man its long walls. This attack was unexpected, Sindhia’s main force was engaged elsewhere, and

very few defenders seem to have been in the fort.

While Captain Popham waited for the rains to break, he worked out a scheme for the reduction of the fortress.(9)

Presumably, he did this in agreement with the Rana, because during both the planning stages and the attack, he made use of spies and guides supplied by him (6).

On

the night of

Fig. 2. An old photograph of the

Man Mandir in

up ‘windows’ are where

the Mughal prison used to be. The main

gate is below

the towers in the

foreground. (Copied from “Romance of the Fort of

There is no mention of the Rana of Gohad’s army in these and most other English accounts of this victory. However, if we would take issue with English historians who ignored the part played by the Rana and his army, maybe we should bear in mind that a Jat account of the same event states that ‘After having taken several other forts Chhatar Singh sent in 1780 an army under Brajraj Singh against Gwalior. Brajraj Singh was killed in the war with the Maratha army commanded by Raghunath Rao, but on 4 August 1780 (2. Sha'ban 1194 AH) the Jats captured Gwalior Fort’. (HH). Should we assume that Captain Popham’s men took no part in it, then?

From information supplied by Hans Herrli, it would seem that all Jat accounts, like the one quoted above, plainly credit the victory to the Rana of Gohad’s army. The truth may well be that both forces were involved. (6). Given that Captain Popham had been sent to Gohad in a supporting role, with only 2,400 men and no battering train, co-operation between the two forces appears to be the most likely scenario. Taking together a number of accounts of the ‘battle’, it seems likely that there were few troops to defend the fort, many or most of those within the fort may have been ‘chaukidars’ or night-watchmen, and the military defenders consisted mainly of cavalry encamped without the walls, which were easily overcome by the Rana’s army (11). The commotion caused by this encounter would have distracted the garrison long enough for Popham’s escalade to succeed, after which, having just seen the Maratha cavalry overwhelmed by the Rana’s forces, they put up very little resistance. Fighting was over almost as soon as it started, and casualties were astonishingly light. It seems quite possible that the garrison surrendered to Popham almost as soon as he set foot on the fort, and that somebody soon opened the gates to allow the Rana and his army to enter and take over the ‘impregnable fortress’. It is not impossible, of course, that treachery was also involved. Muhammad Din’s eye-witness account seems to support this interpretation. (11)

Incidentally, we might well ask whether, with the Rana’s army on the spot, and with their blood up, the English had any choice but to allow him to take possession. Perhaps it was not a matter of ‘handing it to’ the Rana, but of Captain Popham not having the troops that would have been needed to prevent him taking it, even if he had wanted to do so.

---

Meanwhile,

efforts by the English to cement an agreement with the Marathas, employing Raghuji

Bhonsle II, Raja of Nagpur, as a negotiator, were proving infructuous, partly

because of the Nagpur Raja’s equivocating attitude to the peace process. During, and probably partly because of the

stalemate, “

On

The

terms referred to above contained a contradiction within themselves, as

By this treaty,

This decision suited Sindhia

well enough, and he sent De Boigne, one of his most successful generals, to

invest and recapture the ‘impregnable’ fortress. After a protracted siege,

Not only did De Boigne

recapture Gwalior Fort, but an army under Alijah Srinath Mahadji Sindhia attacked

Gohad itself, towards the end of 1784 AD. (AH.1198/99)

and occupied Gohad Fort

on

The

uneasy peace between the Marathas and the English continued until 1802 AD.,

when the English again declared war against the Marathas. Mahadji Rao had died in 1794 AD., and his

nephew, Daulat Rao Sindhia, was now in charge.

Daulat Rao shared his deceased uncle’s determination to rule the whole

of northern

The War between the English and Sindhia was brought to an end by the treaty of Surji-Anjangaon,

which was signed on

Fig. 3 . A view of the Man Mandir

taken in 2006, showing the improved approach road to the main

gate. The Lashkar area is to the right of the city

buildings in the background and to the south of

the Fort, and is now an

integral part of the city.The fort’s fine defensive

position, atop a steep

300 ft. Hill is clear in this view.

Subsequently,

a dispute arose with Sindhia concerning a clause in the treaty of Surji-Anjangaon

by which he had agreed to renounce all claims on his subsidiaries with whom the

English Government had made treaties. Sindhia

now insisted that the Rana of Gohad could not be included under this clause,

because ‘the pretensions of that family had been extinct and their territories

[had been] in Sindhia’s possession for the past 30 years’. This was incontrovertible, and the English

gave way to Sindhia’s legal argument and abandoned

This new arrangement suited

both the English and Sindhia because it left the Chambal as a fixed, recognisable

border between their territories, which ought not to lead to misunderstandings

and disagreements in the future. It

seems that the Rana was given little opportunity to do

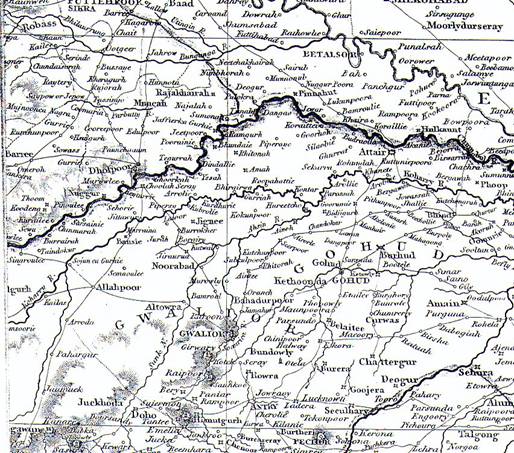

other than agree to move home. Please see

the map below (Fig.

4.) showing the relative positions of

Fig. 4 This map, copied from a map dated 1786,

(12), shows the relative positions of

(Courtesy

Frank Timmermann and

The chronology

of the Jat overlords of Gohad. (1)

Dates are all AD.

I

append below what I think is probably the most accurate chronology available of

the last few chiefs and Ranas of Gohad, earlier chiefs (back to 1505 AD.) being

irrelevant to our present subject. This chronology

was taken from the Wikipedia entry under the article ‘Jatland’,

and it largely agrees with most others available. (2) Chronologies exist showing the reign of Rana

Kirat Singh beginning as early as 1785 or 1788 AD., but

the correct date is almost certainly 1803 AD.

The date of the Rana’s move to Dholpur is stated

as either 1805 or 1806 AD. in different histories, but it seems most likely

that the offer was made in 1805 AD., but the actual move did not take place

until 1806 AD. The spelling of the

chiefs’ names varies from one account to another. I have tried to use the most widely

acceptable spellings in modern usage.

Bhim Singh, 1707-1754 or 56

Girdhar Pratap,

1756-1757

Chhatar Singh,

1757-1785

Interregnum,

1785-1803 AD. (Described as a period of ‘rebellion

and anarchy’.)

Kirat Singh,

1803-1805 (Kirat Singh was offered

Dholpur in place of Gohad in 1805 AD., but he did not move there until 1806 AD.)

Documentary and other evidence for the occupations.

First occupation, 1761 to 1765 AD., AH. 1175 to 1179. The two Jat occupations of Gwalior Fort mentioned above (1761 to 1765 and 1780 to 1884 AD.) are disputed (or at least, ignored) by some Maratha historians. They are, however, a well-documented and properly established part of historical accounts written by English, Jat, and some other Maratha writers. There is concrete (actually stone) evidence for the occupations, within the fort itself, in the form of the Chhatri of Rana Bhim Singh, who was Rana during the first occupation, and which is mentioned above (Fig. 1A). This was erected during the second occupation (Rana Chhatar Singh). There are other buildings and inscriptions inside the fort, also erected by the Jats during the two occupations. (HH)

Second occupation, 1780 to 1784 AD., AH1195 to 1199. In further support of the actuality of the Jat occupations, Hans Herrli, who has made about twenty lengthy visits to India over many years, spending weeks or months each time studying the history and coins in Haryana, Rajasthan and central India, and who has made a specific study of matters surrounding the Jats and Gwalior, has confirmed that “The Jat Sawaj Kalyan Parishad (Association of Jats in the Gwalior region) organises an annual fair on Rama’s Birthday (Rama Navani) in memory of Gwalior Fort’s occupation by the Jat rulers Bhim Singh Rana and Chhatar Singh Rana of Gohad State.”(2) This fair, and historical studies supported by the Jats, are stated by Hans Herrli to have been a reaction against Maratha authorities and writers trying to suppress the fact that the Marathas lost Gwalior Fort twice to the Bamraulia Jats, whom they regarded as ‘inferior’. Hans has also seen and confirmed the existence of the Chhatri and other memorials within the fort itself, put there by the Jats during the first and second occupations. The Jat group mentioned has a web site (including ‘Jatland’) on Wikipedia, and. material on those sites further confirms this version of events. (2).

In the period from 1802 to 1806 AD., however, we find universal agreement that there was no Jat occupation of the Gwalior Fort, and that it was retained by the English from the day they took possession of it in November 1802 AD. until they returned it to Daulat Rao Sindhia in November 1806 AD

The coins, and numismatic evidence for the occupations.

As

coin aficionados, we are naturally specifically

concerned with matters numismatic, and the question arises as to what

numismatic evidence we might have for the two Jat occupations of Gwalior Fort.

First occupation, 1761 to 1764/65 AD., AH. 1175 to 1179. Coins were certainly struck

in the Gwalior Fort mint during that period, and are quite commonly met with. Although there is a sprig-like mark on the

obverse of some (but not all) rupees bearing relevant dates, that mark has not been

specifically associated with the Rana of Gohad.

In any case, these same coins often bear other small, typically Maratha

marks. Therefore, we must conclude that

the first occupation of Gwalior Fort by the Rana of Gohad, Bhim Singh, probably

left us no conclusive numismatic evidence.

However, we need to remember that the inclusion of distinguishing marks

on Mughal style coins issued by Mughal successor states was by no means

universal at that time. On balance, it seems

appropriate for those coins of Gwalior Fort mint dated within the relevant time period (roughly 1761 to 1764 AD.), to be attributed to

the Rana of Gohad, Chhatar Singh, and not to Sindhia. This has not been the case, up to now.

Second occupation, 1780 to 1784 AD., AH1194 to 1198. The coin shown below in Fig. 5. is a silver rupee weighing about 11.2 grammes and measuring about 21 to 21½ mm in diameter. The obverse bears the date (AH.) 1195, with the ‘Haft Kishwar’ legends and name of the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II. In the middle line is the cinqfoil flower with curved stem that we see on the Gwalior Fort rupees struck during the reigns of Mahadji Rao and Daulat Rao Sindhia. The reverse has a portion of the usual formula and his regnal year 23. In the bottom line is the mint name ‘Gwaliar’, quite clear and virtually complete. To the left of the regnal year is the pistol mark typical and diagnostic of coins commonly attributed to Gohad and Dholpur mints before and after the date of this rupee. In this instance, the pistol is not upside-down. This shape of pistol mark was a symbol used by the Bamraulia gotra of the Jats. The Ranas Bhim Singh (1707-1756 AD.), Girdhar Pratap Singh (1756-1757 AD.), Chhatar Singh (1757-1785 AD.) and Kirat Singh (1803-1836 AD.) belonged to different families, but all were of that clan. (HH, 2) The pistol on this coin, as on all Gohad and Dholpur coins where it is found, is distinct in style, and can be readily differentiated from those on Maratha coins, such as Agra paisas struck under Sindhia’s Governors, where the shape of the pistol is very different. This pistol is certainly the mark of the Gohad Rana, and not of Sindhia

Fig. 5. A rupee of

It bears the

pistol typical of the Rana of

Gohad’s coins, and later, those of

respects, it is similar to the

Krause coin numbered KM. #5.2, and this suggests that

KM’ #5.2 has been attributed

to the wrong mint.

Dating

evidence. The 1st of Muharram (the Muslim New Year) AH 1195

fell on

In

the 4th

edition of

“The

Standard Catalogue of World Coins 1701-1800”

(16)

there are

illustrations of another example

of an

exactly similar type, numbered KM

#5.2

with the same

date,

which

was plainly

struck from a

different set

of dies

from the

coin shown above. It

therefore seems likely that this type of

coin was issued in some

numbers, although they are not at

all common today. Might

these coins that vouched

for the fact that

Chronology of marks and symbols. Rupees

of Gwalior Fort mint, prior

to the occupation, do not show a scimitar to the right of Julus. The last recorded date of a Sindhia coin without that mark is AH. 1191, regnal year.19.

The earliest published date of a Sindhia rupee with the scimitar mark is AH. 1197, regnal

year 25. The rupee illustrated in Fig. 5

above, with the pistol mark of the Ranas of Gohad, fits in between these two

types, and is distinct from both. (16)

In addition

to this rupee, there are, in the coin cabinet of the

Fig. 6. Paisas of the

(

the kind permission of Dr. Mark Blackburn, Keeper of Coins and Medals Dept

. Photographs courtesy of Shailendra Bhandere).

Below (Fig. 7A and 7B) are two coins from

the collection of the

7A.

A copper paisa of Gohad mint, dated AH. 1197, regnal year 2x.

(similar to Krause KM.2).

7B. A silver rupee, also of Gohad

mint, dated AH. 1185, regnal year 13.

Both coins 7A and 7B bear the pistol symbol.

7C. A silver rupee dated AH. 1181/9

and is of the type that preceded 7B

above. This type does not bear the pistol mark. The last reported coin of

this type has the regnal

year 10 of Shah Alam II.

Fig. 7A and 7B: Photographs supplied by and used courtesy of Shailendra

Bhandere, Assistant Keeper,

The second coin (Fig. 7B.) is a silver rupee dated AH.1185, regnal year 13. It also bears the Jat pistol symbol on the obverse, and the mint name ‘Gohad’ (GWHAD) in full. It is the earliest coin bearing the Bamraulia Rana’s pistol symbol to be published so far. Two other similar Gohad rupees in the Ashmolean collection dated regnal years 8 and 10 (SB), and one dated AH. 1181/9 in my own collection (illustrated above as Fig. 7C.) do not bear this symbol. This is the type shown in Krause catalogues as KM. #4. The chronology of these coin dates confirms that documented by historians, and summarised above. The status and identity of Krause KM. #5.1 and the date listing associated with it requires clarification. A Gohad rupee published in the JASB-NS for December 1910 is also relevant here. (17).

1802 to 1806 AD. This time there was no occupation by the Rana of Gohad. On the contrary, the fort is stated universally to have remained in English hands throughout. Some rupees struck during this period bear a mark, which might be a Persian ‘kaaf’, or ‘K’ on the obverse. See Fig. 8 below.

Fig. 8. A rupee of the British occupation of 1802 to 1804, bearing the date

AH. (121)7,

and regnal year 45 of Shah Alam II, which began on

displays a mark like a Persian ‘Kaaf’, in the loop of the ‘L’ of ‘Fazl’.

The name of the

Rana of Gohad at this time was Kirat. The date combination covers the period from

According to most of the published chronologies of the Gohad

overlords, including the one reproduced above; there was an interregnum from

after Chhatar Singh’s death in 1785 AD., until 1803 AD. This is reported to

have been a period of ‘anarchy’, unrest and disputation. Kirat Singh is usually said

to have been ‘chosen’ as Rana by the nobility of wreck of the Gohad

polity in 1803 AD. Under the

circumstances of the alliance between the English and the Gohad Ranas, and

their joint occupation of the

Fig.9. This is a Gwalior Fort rupee, dated

AH. (1)218, regnal year 46

(1803/04 AD,) and shows a

sword of a completely different design from

that usually seen on rupees of this series, to the right of

‘Jalus’.

Photograph

courtesy Jan Lingen.

Fig. 9 shows yet another

type of rupee struck at Gwalior Fort.

This one has a straight sword with hand-guard, which resembles those used

by officers of the British Army. This

design of sword could therefore symbolise that this type of rupee was struck under British authority. The date of the rupee is AH.1218, regnal year

46, which date combination runs from

The British, on taking over native mints at

the end of the Maratha and other wars, did not always alter the issues of those

mints, especially if they were earmarked for early

closure. This could have been the case

here, as

Explanation

of the dating of coins struck in the name of Shah Alam II.

Prince

Ali Gauhar (pre-accession name of Shah Alam II) proclaimed himself Emperor while

he was in

There is a gap in the date run of the published and unpublished Sindhia copper and silver coins of Gwalior Fort, which nicely corresponds with these distinct issues of the Gohad Rana. (Lingen and Wiggins numbers 01, 02 and 03 of Gwalior Fort, Krause numbers KM.55, 56 and 57.1 for rupees, and the above coin dated AH. 1194 along with KM.54 and Lingen and Wiggins type 04 for the paisas). (16, 20)

Conclusions.

From the foregoing summary of the history,

and the evidence adduced from the coins themselves (21), it is certain that the

rupee and the paisas illustrated above, and dated AH. 1195/23 are coins of the

Rana of Gohad, Chhatar Singh, struck in 1781 AD. at

the

We cannot

legitimately continue to refer to the coins of the Rana of Gohad as

Coins

struck by the Gohad polity up to its capture of Gwalior Fort in AH. 1194 can only have been struck at Gohad. Those struck during the occupation could have been struck at either Gohad or

References.

(1) ‘The Jats – Their Role in the Mughal Empire’ by Girish

Chandra Dwiverdi,

(2) ‘Wikipedia’ entries for Jats, ‘Jatland’ and ‘The Jat Sawaj Kalyan Parishad’. See also ‘Jat Wiki’.

(3) ‘History of the Marathas’ by James Grant Duff, reprinted Karan Publications,

(4) ‘Marathas, Marauders and

State –Formation in 18th Century

(5) ‘History of the Marathas’ by James Grant Duff, reprinted Karan Publications,

(6) ‘An Historical Sketch of

the Native States of

(7) “In order to form a barrier against the Marathas, Warren Hastings made a

treaty in 1779 with the Rana, and the joint forces of the English and the Rana recaptured

(8) The rank of this officer is variously reported as Major, Captain and Colonel. The confusion possibly occurred because these events were recorded by the writers at different times, some long after the events described, and after Captain Popham had been promoted. His rank at the times of writing have probably been inserted into those accounts.

(9) ‘History of the Marathas’ by James Grant Duff, reprinted Karan Publications,

(10) ‘The Imperial Gazetteer of India’, HMSOSI in

Council, Clarenden Press, Oxford, reprint edition, Today and Tomorrow’s

Printers and Publishers, New Delhi, Vol.12, p.441

(11) ‘The Travels of Dean Mahomet,

A Native of Patna in Bengal, Through Several Parts of India, While in the

Service of The Honourable The East India Company’ Written by ‘Himself’, 1794,Letter XXX. www.eScholarship.org/editions.

(12) ‘History of the Marathas’ by James Grant Duff, reprinted Karan Publications,

(13) ‘The Hind Rajasthan’, compiled by H Mehta, 1896, publisher

unknown. p.414-415 tells us that, under the

terms to which the English and Sindhia were about to sign up, the Rana was to

be “allowed to retain the hill-fort of

(14) ‘Romance of the Fort of

(15) Several accounts give the name of one or more of the Ranas of Gohad as Lakindar (or Lokinder) Singh. In fact, at the time of Panipat and the first Jat occupation of Gwalior Fort, the Rana’s name was Bhim Singh, at the time of the second occupation he was Chhatar (Chhatar) Singh, and at the time of the third Maratha War he was Kirat Singh. Lokinder is a title held by all Jat rulers of Gohad, in the same way that all rulers of Bharatpur were entitled ‘Mahinder ‘or ‘Brajinder’, and the rulers of Datia were also all entitled ‘Lokinder’. There are other examples, as rulers of all Jat houses had titles ending in ‘-inder’ (SB)

(16) ‘Standard Catalogue of World Coins’ 18th

& 19th Century editions, and ‘South Asian Coins...’, 1980 to date. Krause Publications,

(17) JASB Numismatic Supplement “Notes on some Mughal Coins” by B Whitehead. Coin no CN054, p.674, JASB Dec. 1910, Plate XLV.

(18) ‘Forgotten Mughals’, G

(19) ‘Shah Alam and the East

India Company’, by Kalikinka K Datta,

World Press,

(20) ‘Coins of the Sindhias’ J Lingen & K

Wiggins, Hawkins Pubs.

(21) A very knowledgeable numismatist once told me, “If you want to know the truth, you must go to the coins”. I have found it to be useful advice, as coins rarely lie, even though they sometimes ‘bend the truth’ a little. I pass Shailen Ji’s advice on as a ‘Word to the Wise’

Other Material consulted, cited and quoted.

(i) ‘The Call of Gopachal’ by Thakur Shri Yashwant

Singh, Vijay Singh Chauhan,

(ii) Private correspondence with Hans Herrli.

(iii) ‘Warren Hastings

and British

(iv) It

has proved

difficult to find detailed information concerning

the Bamraulia

Jats

written in or translated into English.

There are three

histories that are said

to be reliable.

They are

in Hindi and

English translations do not appear to

exist.

Details below were supplied

by Hans Herrli, and

are included here because

there are certainly a goodly number of

readers of the JONS who do read

Hindi, and may find these

references

helpful:-

1. ‘Gohad ke jaton ka Itihas’, Dr.

Ajay Kumar Agnihotri, Nav Sahitya Bhawan. (

2. ‘

3. ‘Jat – Itihas’, Dr. Natthan Singh, Jat Samaj Kalyan Parishad. (Gwalior, 2004.)

Acknowledgements.

SB, HH and JL. I would like to thank Shailendra Bhandere, Hans Herrli and Jan Lingen for their help in supplying photographs, advice and data. Shailen Ji has checked my text, and suggested several corrections and alterations, for which he has my thanks. Jan Lingen provided a useful table of Jalus commencement dates for the reign of Shah Alam II, thus saving me the tedious job of constructing my own. Thank you, Gentlemen.